Warning Shot: SpaceX’s Unexpected Failure and Industry Impacts

With SpaceX resuming launches after a two-week break, it’s time to see what, if any, impacts two weeks of no Falcon 9 launches might have had.

The Numbers

The impact on SpaceX’s launch cadence is the easiest to calculate. For most of 2024, SpaceX averaged slightly over 11 Falcon rocket launches per month from January through the end of June. February saw the lowest number of company launches–nine. SpaceX conducted the highest number of launches during May–13. The company had conducted three launches in July (including the “troubled” launch) before the two-week hiatus. SpaceX’s recommencement of launch operations on 27 July will put the company at four launches for that month.

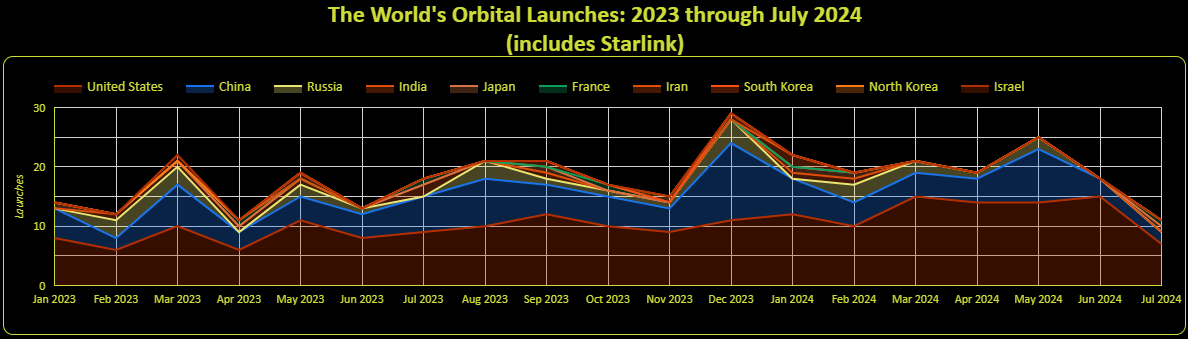

In the context of all orbital launches conducted in 2024 and comparing them with 2023, the dropoff in U.S. launches for July 2024 is very obvious when depicted in the following graph:

And, yes, overall monthly U.S. orbital launches conducted in 2024 so far have significantly exceeded 2023 U.S. launches. However, once SpaceX was out of the picture, orbital launches worldwide were nearly non-existent during the two weeks the company paused. The exception was the launch of a Long March 4B (CZ-4B) from Taiyuan, China. Still, looking at launches from China for the month, it’s unclear why the country’s launches dipped in July compared to the six launches it conducted in July 2023.

If we take SpaceX’s launch average for 2024, two weeks is the span in which the company usually conducts about five to six Falcon 9 launches. With seven launches in July, it’s still four behind its 2024 monthly launch average. In other words, SpaceX was already behind in its goal to reach 144 launches in 2024, and now it’s further behind.

As explained in a previous analysis, there’s reason to believe the company will increase its launch cadence during the latter half of 2024. It will probably exceed its 2023 launch record; however, SpaceX must push harder than usual to reach its 2024 goal.

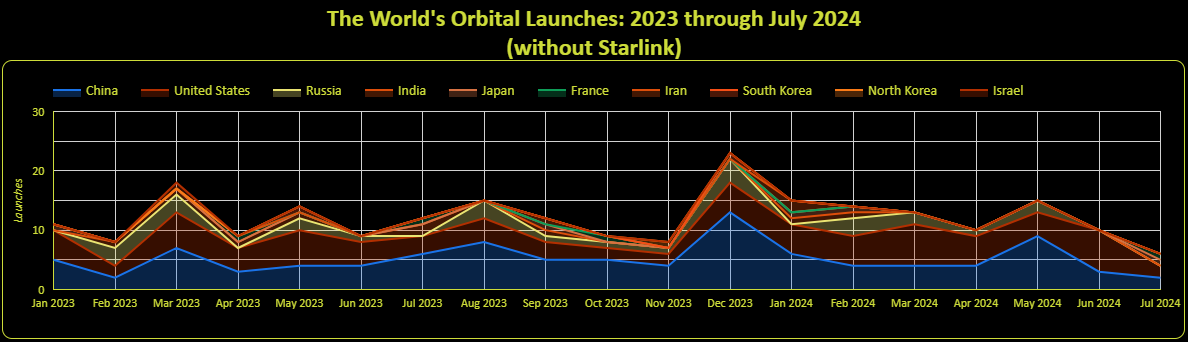

Regarding launches other than those conducted for SpaceX’s Starlink constellation, people might be surprised that the company averaged about three external customer launches per month for the first six months of 2024. It conducted just one external customer launch in July 2024. Subtracting Starlink launches from overall U.S. launches results in a chart depicting numbers more comparable (or falling behind) with launches from China during the same period in 2024.

Customer Considerations

Although there may be fewer external customers for the remainder of 2024, SpaceX will prioritize delayed external customer launches over Starlink launches. After all, it’s not like the company is playing catchup, considering its lead in deploying LEO satellites with internet relays. Despite rescheduling those Starlink launches, SpaceX will still deploy more Starlink satellites in 2024 than any potential competitor.

Potential SpaceX customers will likely consider the misbehaving second stage when deciding whether to use SpaceX. However, I suspect it will be a minimal consideration, if only because there are no other choices—at least, not yet. After the pause, SpaceX conducted three Starlink launches for the remainder of July 2024 (three launches within two days). None of those launches had second-stage issues.

I suspect those three “in-house” launches are meant to reassure existing and potential customers that SpaceX has fixed the second-stage issue. While it may be unfair to legacy launch providers with new systems, neither Arianespace nor ULA could have demonstrated a root-cause fix as quickly or concretely as SpaceX just did.

While Ariane 6 and Vulcan have launched once, the companies launching them are on a schedule allowing system tweaks, mission assurance verification, etc. This means they (Arianespace and ULA) are each moving slowly toward their second launches (to be fair, SpaceX also dallied between its first and other launches). They may significantly ratchet up the cadence for their systems after those launches. However, customers might have to wait for an opening between these companies’ government contracts and Kuiper obligations. For businesses looking for a ride to space sooner rather than later, waiting for a ride from the legacy providers might be the difference between a business plan’s success and failure.

The Warning Shot

As for other possible impacts from SpaceX’s Falcon pause, I suggest the biggest one might be a wake-up call to government customers. They likely already recognized that relying on a single company and its rocket for ISS crew transportation or national security launches was not ideal. The pause provided a glimpse of possible terribleness. Nothing was launched from the U.S. during those two weeks. The U.S. had no launch capability during those two weeks. But since no government launches were scheduled during that time, there probably was little squirming about the lack of launch capability.

But what if NASA had needed to evacuate a couple of astronauts from the ISS during that time? Would the FAA have given the go-ahead? Would SpaceX have figured out enough to give 95%- 100% confidence in a functional second stage? More confidence than using Starliner to return those astronauts?

With no happiness, I also suggest that the second stage malfunction was a warning shot to those who rely on U.S. rockets for transportation. SpaceX doesn’t know about the unknowns–no company does. While it’s been more successful than most, Murphy still showed up and punched SpaceX in the kidneys, creating an unscheduled U.S. launch moratorium.

Much has been written about how NASA has successfully managed to get two crew transportation systems running to avoid such a scenario–but based on just how gingerly the space agency appears to be treating Starliner, does it honestly have two functioning crew transport systems to rely on? Or is there one, with the other merely checking the box? And the reliable one is…not as reliable as assumed?

Something similar has happened with the commercial cargo program, too. Theoretically, two systems can launch cargo capsules to the ISS. However, only one has been conducting that mission for the past year or so. This is not to condemn NASA for its efforts but to note that its commercial programs require more care and feeding than before to have a genuine backup launch capability instead of just telling the public and Congress it does.

However, it has been more proactive than the DoD, which has reverted to embracing a monopoly for its missions. To be clear, issuing potential contract awards for non-existent systems doesn’t appear to be working to gain redundancy. The DoD is hoping that Vulcan will become reliable. While U.S. military operations could probably continue using ULA’s Vulcan if Falcon 9 became unavailable again, the DoD wouldn’t launch nearly as often. It would need to budget more to launch. Maybe that’s not a problem.

I didn’t believe that SpaceX would take long to troubleshoot its problem, but my belief and SpaceX’s quick response aren’t the point. Things could have been worse. We should be thankful they weren’t and that important missions were not impacted. But the U.S. needs to be serious about gaining some more rocket launch alternatives.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), I appreciate any donations (I like taking my family out every now and then). For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU from me and my family!!

Comments ()