The SDA’s Inertia-imposed Challenges

There will be no article next week because I’m on Christmas holiday. For those celebrating, have a lovely holiday!

The Space Development Agency (SDA) has pointed, over and over again, at one of the key challenges it knew its plans would face: satellite manufacturing supply chains. In March 2022, C4ISRNet.com reported:

“A senior defense official told reporters March 15 that SDA is closely monitoring the supply chain for all of its satellites. Parts shortages, particularly for electronics, are a concern for the agency.”

The U.S. satellite manufacturing supply chain has been a persistent challenge for the SDA since the beginning, with SpaceNews reporting the latest supply chain story,

“The SDA is becoming the “canary in the coal mine” for broader industrial base challenges, uncovering deep-seated issues resulting from decades of industry consolidation aimed at maximizing efficiency.”

Conditions for Consolidation

Consolidation is a part of the problem, to be sure. The SDA won’t fix it because the agency has contracts with the consolidated space industry. However, there is another problem that the SDA is wrestling with: U.S. military expectations for satellite manufacturing in the past that created the conditions for consolidation.

Not even ten years ago, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) deployed an average of eight satellites per year (from 2013 through 2017). It was not unusual for DoD satellites to be deployed late and less usual for satellite manufacturers to face significant consequences for delivering a late product.

Worse, the slow production was for established programs, such as GPS or geosynchronous communications satellites. Although the DoD and contractors were familiar with the missions and technologies required for these programs, they still exceeded budgets and milestones.

The DoD’s embrace of these slow, high-cost programs made the military satellite manufacturing “market” a place where only large companies could succeed. Small manufacturers and startups with limited resources (people and money) would have found the typical military space acquisition timelines and processes (many, many miscellaneous reviews) uninviting.

A small company’s acceptance of those timelines would have been suicide (a reason why subcontractors work within larger companies). However, large diversified aggrecorps like Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman can afford the comically drawn-out DoD processes. They have departments full of people dealing with the government’s eccentric and inefficient processes.

The above examples only serve to demonstrate that one thing begets the other. The DoD’s acquisitions agencies equated lengthy program execution with due diligence (instead of increased budget extraction) and encouraged longer schedules. The only companies that could afford to string out these programs were the large ones with plenty of resources, who provided (eventually) a satellite or two. By the DoD’s measure, the system worked.

However, another side effect of the system was that fast, responsive supply chains were never needed. DoD satellite programs that took years to produce a single satellite weren’t developed with a robust supply chain in mind. That set of circumstances meant no satellite manufacturing supply chain was in place to meet the SDA’s much faster program schedules.

Choices of Convenience?

The SDA’s management appeared to understand all this, although things were already changing at its founding. From 2018 to 2021, the DoD deployed an average of 21 satellites annually (a nearly 163% increase from the 2013-2017 average). Twenty-one satellites per year was a better average, but the SDA’s Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) called for many more satellite deployments (about 1,000 by 2026). It would have taken the SDA nearly a half-century to deploy PWSA at that average deployment rate.

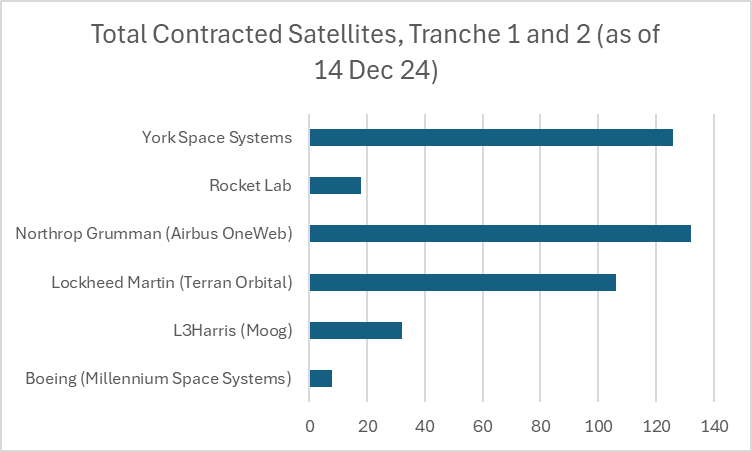

The SDA eventually awarded contracts for hundreds of satellites for the PWSA’s Tranche 1 and 2.

The problem with the awards is in the above graph. It was summarized in a 2022 article regarding one award cycle:

While the decision may have appeared to favor incumbents, Turner said, the selection was based on which companies wrote the best proposals, which is the government’s prerogative.

That is why the SDA’s contracting mechanisms won’t address the consolidation problem in the satellite manufacturing industry. Four of the six companies the SDA awarded contracts to were consolidated (the favored incumbents that the SDA’s Frank Turner acknowledged).

Four of the SDA’s Tranche 1 and 2 awards went to the legacy companies, with the most going to Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. Of the six, York Space Systems and Rocket Lab are the only “new space” companies with SDA Tranche 1/2 contracts. Of those two, only York has a comparable award share to Lockheed or Northrop.

The companies listed in the parentheses are the subcontractors to or acquisitions of the larger companies. I had initially noted this relationship between legacy and new space satellite manufacturers in “SDA’s Nudge Exposes Legacy Challenges.” It was logical for the old companies to “buy into” the small satellite manufacturing market because their in-house offerings were…lacking. But buying into small satellite manufacturing doesn’t make these old companies smallsat manufacturing pros.

Instead, the SDA finds itself dealing with legacy companies that are unused to managing substantial and responsive satellite manufacturing supply chains. Additionally, they need to produce satellites much quicker than before (presumably a reason for acquiring a smallsat manufacturer). So, while they’ve bought the capability, they don’t seem capable.

Some Better Reasons, Perhaps?

But, the reason the SDA’s management provides for selecting the old companies is ridiculous–they “wrote the best proposals” (whatever that means). Of course, they did! Writing winning proposals is something they understand. They have departments dedicated to proposal writing. The “best proposals” do not imply the companies are great at smallsat mass manufacturing, merely that the companies have ideas to address the SDA’s challenges and can word the proposals in a way pleasing to the SDA.

The reason for selecting legacy companies highlights that some of the SDA’s problems are self-inflicted. For all its talk of incentivizing speed and technical maturity, the agency seems to have fallen into a trap in its contract awards. It didn’t appear to recognize that while smallsat manufacturing startups might not float the “best proposals,” they might have better solutions than the incumbents. It didn’t seem to understand that consolidated companies were probably not the industry movers it needed.

Even if those legacy companies conveniently just acquired smallsat manufacturing companies prior to the awards. Also pertinent to the decision is that a few of those smallsat manufacturers have yet to prove they can produce satellites in the numbers required to get to 1,000…by 2026. That requires manufacturing about 83 satellites per month.

Airbus OneWeb has already proven it can come close to that goal on its own, with the ability to manufacture two satellites per day (~60/month). If Northrop Grumman doesn’t mess (integrate) with OneWeb’s product too much, they will hit their SDA contract obligation. On the other hand, Millennium Space Systems advertised it could produce 60 satellites per year (five per month). Millennium provided that number before opening its newest factory, but the company has not provided a manufacturing rate.

Assuming a minimum of five satellites per month means Millenium could manufacture at least 60 by the time 2026 rolls around. However, it’s on the hook for much less than that currently (eight). Terran Orbital comes much closer, advertising it can manufacture 20 satellites per month–still inadequate for the SDA’s needs, but (in theory) it should meet Lockheed’s contract obligations. However, its current rate averages about seven satellites per year since 2018.

Ultimately, the SDA addresses a formidable challenge: developing and supporting a satellite manufacturing base and supply chain that never existed prior to the SDA. Aside from OneWeb and SpaceX, no other company, including those contracted by the SDA, has a proven manufacturing rate close to what the SDA needs. Those contracted by the SDA have their own supply chain bottlenecks.

Despite some of its self-inflicted problems, the SDA is generally successfully enforcing a different view on and process for acquiring military satellites. Maybe the incumbents will eventually get the memo since the U.S. military satellite deployments have increased, not because of their efforts. That should be motivating.

More will be said about that in the following article.

Comments ()