Spacecraft Operations Growth: a Case for Optimism?

If you haven’t visited the Global Space Activity Dashboards lately and you like space data, then maybe you should take a peek. I’ve added dashboards for each year from 2019-2023. 2024’s activities are there, of course, and continue to be updated as launches happen. Please take a look.

In my post “2023: Pointing to 2024’s Space Activities” two weeks ago, I guessed that there would be more spacecraft operators (launch customers) and that the diversity of the types of missions they conduct would also increase. I used most of the data I gathered from 2023 to make that guess.

However, a single year doesn’t make for a trend. Also, the data I based my guesses on were the launch offerings, primarily in the form of rideshare from Arianespace, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), and SpaceX. I guessed that as long as these launch services offer routine rideshare launches, more customers would flock to them.

However, other data backs up my guess. In this case, however, it’s in the form of the history of spacecraft operators (the companies/organizations monitoring and sending commands to spacecraft) over the past four years. To be clear, four years still is somewhat sketchy for trends, but it’s what I have. All charts in this article reference the number of spacecraft operators, not the spacecraft they deployed.

Spacecraft Operator Growth: 2019-2023

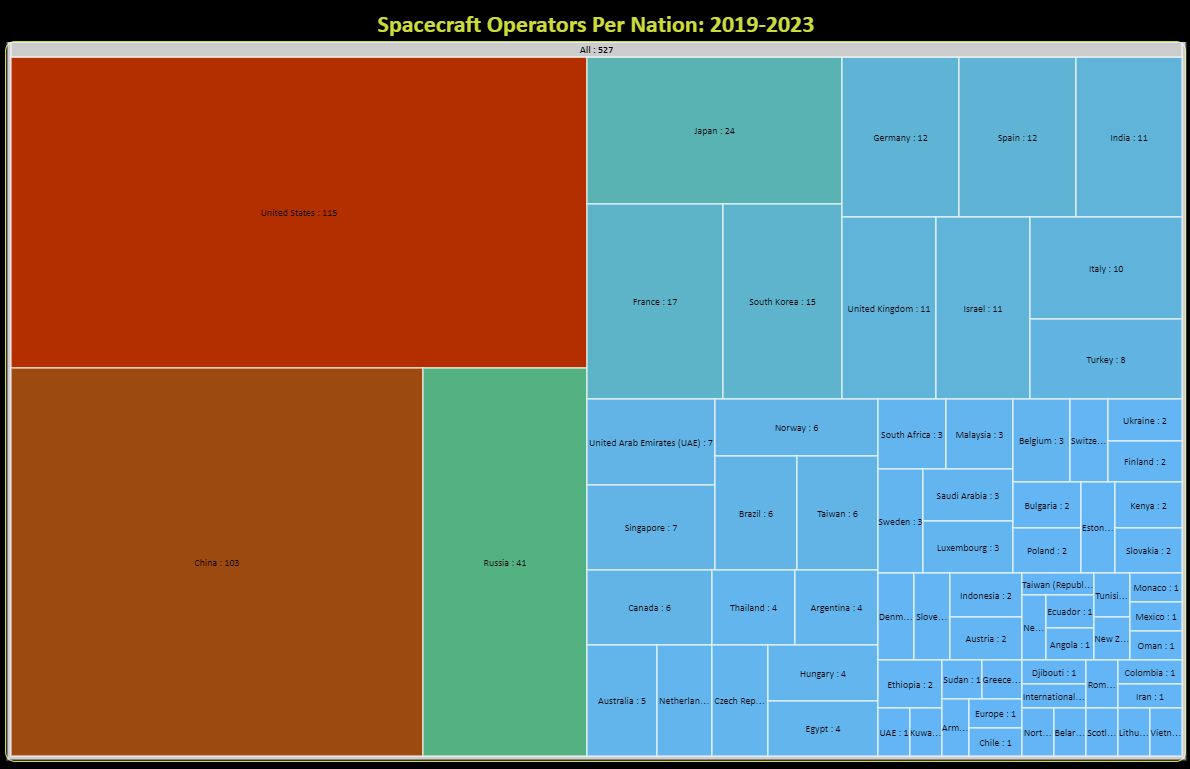

From January 2019 through December 2023, about 527 spacecraft operators from 72 nations deployed spacecraft into orbit (in the treemap below). Over 40% of those spacecraft operators deployed spacecraft in 2023 alone. Please pardon the hard-to-read font.

The number of spacecraft operators and nations might be surprising. But, at least since 2019, both categories have experienced growth. While I haven’t gathered data from earlier for Ill-Defined Space, I can observe that when I worked for the Space Foundation from 2014 through 2019, spacecraft operators and the nations that hosted them were experiencing growth.

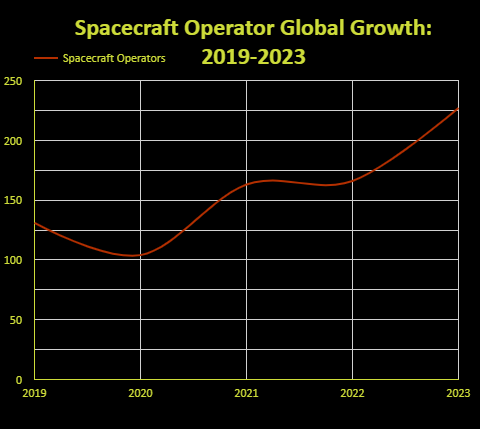

Spacecraft operator growth (since 2019, anyway) is depicted below. The graph counts new and recurring spacecraft operators, so the total number of spacecraft operators per year is more than the actual 527. But the trend over the past four years is generally upward. The dip in 2020 is probably due to the global pandemic–but it’s also a bit shallow.

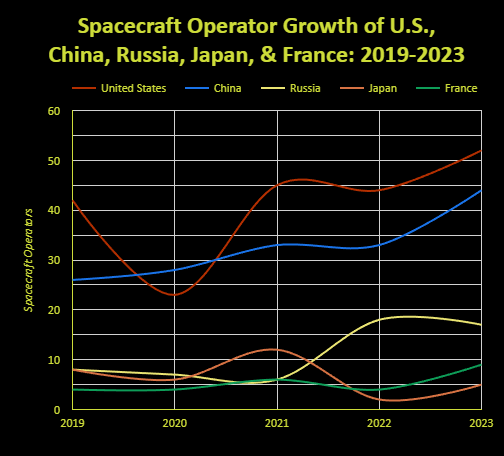

Breaking down the spacecraft operator growth of five countries (of 72) with the most spacecraft operators over the same period shows mixed trends. Two nations stay relatively flat, but three–China, Russia, and the U.S.--show an upward trend. That those three nations have more space operators than most is probably unsurprising. The numbers show that neither China nor Russia are as monolithic in their space operations as some might guess.

It may surprise some observers that in the past four years, nearly half of the 103 spacecraft operators from China were commercial companies. A little over 40% are civil agencies and organizations, such as the China National Space Administration (CNSA), China Meteorological Administration, and various universities and institutes. About ten of China’s 103 spacecraft operators have conducted military space operations.

Russia’s 41 spacecraft operators skew heavily toward conducting civil missions at 76%. Civil mission spacecraft operators include Roscosmos and others, such as JSC Satellite System GONETS, RosHydroMet, and (again) various universities and institutes. Nearly 17% of its operators conducted commercial missions, while, perhaps surprisingly, only 7% (3) were conducting military space operations.

About 53% (slightly more than China’s commercial operator share) of the 115 spacecraft operators from 2019 through 2023 were running commercial missions. However, U.S. civil agencies and universities comprise 37% of U.S. space operators, with military space operations taking the remaining ~11%.

Parsing the Numbers

Overall, China and the U.S. have almost equivalent proportions of space operators conducting civil, commercial, and military space missions. What’s strange is that while U.S. commercial space operators tend to provide services beyond that nation’s borders, it appears that most of China’s commercial space operators don’t.

In other words, most commercial space operator growth in China from 2019 through 2023 seems to have been generated from domestic customers. On the other hand, Russia’s seven commercial space operators have probably suffered from a lack of international customers because of their nation’s adventure into Ukraine since early 2022.

As for the other nations with space operators–they are a reason why I believe there will be more spacecraft operators for this and next year. Consider that many European countries have spacecraft operators and that startups are hobbled because of Europe’s lack of rockets. Maybe even this year, both will move to other launch options if only because waiting for Arianespace costs money.

India also will increasingly have indigenous commercial spacecraft operators deploying spacecraft. The nation’s government is encouraging commercial interest in space for launch and more. Over a hundred Indian space startups have materialized as a result (maybe).

Spacecraft Operator Missions/Services

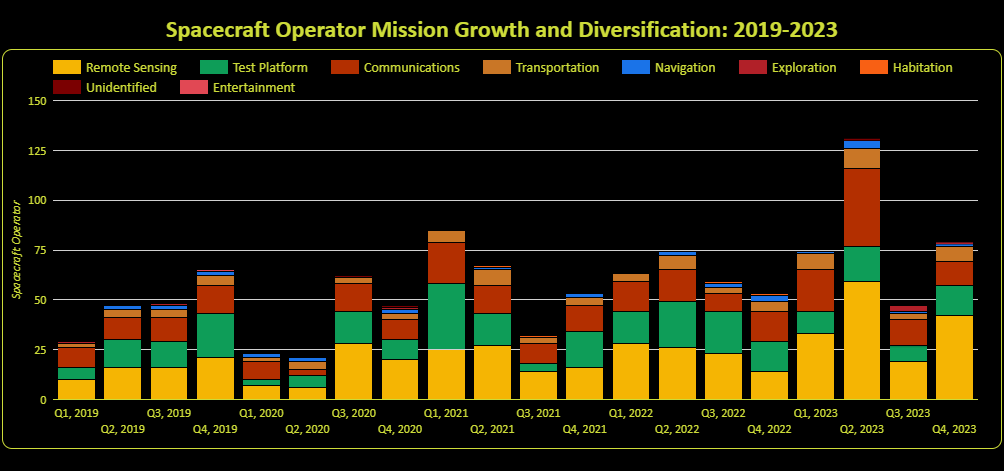

Regarding the kind of missions (services), it may be a coincidence that the number of spacecraft operators offering more services increased through 2023 from 2019 at about the same time SpaceX started routinely launching Transporter missions. Overall, 527 space operators deployed spacecraft into orbit over the years.

Of them, 37% (235) were working with spacecraft with some type of remote sensing payload. Commercial space operators comprise about 35% (less than 90) of remote sensing operators. The next largest share (33%) of space operators were testing spacecraft payloads of all kinds.

Most interesting from the space operators’ test efforts is that about 37% are commercial companies. The overall test share and the commercial sub-share are other reasons to believe there will be growth and diversity in satellite deployments, not just in 2024 but for a few years after, too. The testing indicates space operator interest. They’ve committed the resources to get one or more test spacecraft in orbit.

While that’s no guarantee of success, there are so many spacecraft operators testing payloads that surely a few will deploy operational spacecraft in the future. Again, this test category of payload operators covers all sorts of payloads, such as communications, remote sensing, navigation, and some really oddball ones.

Operators that provide communications services comprise about 22% of spacecraft operators, the third highest mission share. It might seem counterintuitive that services with thousands of satellites in orbit aren’t backed by a corresponding number of spacecraft operators. However, only a few companies are deploying hundreds or thousands of communications satellites. The latest companies are backed by significant resources, perhaps making this type of service seem untenable for startups to attempt.

There are other spacecraft operator service categories, but the one that caught my eye, with just 4% of the operators, was transportation. U.S. spacecraft operators alone, 14 of them, accounted for more than half of transportation-focused operators. Some provided human and cargo transport to the International Space Station. However, other companies provided satellite transportation from a rocket’s insertion orbit to a different orbit altogether, where satellites were then deployed. At least one operated a spacecraft that was supposed to rendezvous with other spacecraft.

Such commercial businesses were unheard of ten years ago, and their existence today, especially since they made up a small part of space operations between 2019 and 2023, shows growth. Its small share also indicates the likelihood of more growth in the future.

Counterbalancing these optimistic numbers is the disconnected nature of China’s space operators. It’s to be expected that its military and civil satellite operations are conducted to further the government’s goals. U.S. government-operated satellites do the same. However, China’s commercial operators, while active in its boundaries, also appear to be noncompetitive external to them.

It’s strange that the nation’s operators comprised nearly 20% of all space operators in the last four years, but seemed to contribute little to the global space industry in services provided. While China’s renowned large population might be able to support such insularity for some time, its space operators are not competing on a global stage. That may imbue in them a weakness and blindness of the true nature of competitive markets they’d be entering, if and when they do enter.

That’s where I’ll leave it. The short history of data I have points to a likelihood of more spacecraft operators joining in with more operational spacecraft. While most seem set on providing more remote sensing services, others will bring services that have never been in orbit.

The caveat is that their reliance on SpaceX’s Transporter service to deploy their spacecraft inexpensively means there’s a limit to how many can be deployed in a year. It’s unlikely to have been reached yet, but the limit exists. As noted in the original article, others are out there who might be able to step in. Whether they can provide rockets as reliable, inexpensive, and accessible as the Falcon 9 remains to be seen.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), any donations are appreciated. For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU!!

Comments ()