Space Zombie Statistics: The Industry of Data Reanimation

For interested readers, Astralytical posted another of my pieces on its site. It’s about that whole “space is hard” cliché and my thoughts about it: Adamantine Space: Oversimplifying Space Industry Challenges.

I realized, while finishing up my master’s degree last week that a few observations are in order based on what I saw as other students researched topics.

This article's primary observation is about students' and the space industry’s reliance on commonly pushed space statistics to bolster their arguments. The problem is that students, like everyone else in life, are under the gun to produce something, and they tend to grab the most conveniently available data. That convenience comes in the form of readily available information yielded through the use of common search terms and popular search engines on the internet.

The data those searches provide usually aren’t the most accurate and are based on irrelevant or non-credible information (sometimes both). However, despite the inaccuracies, the resulting data is, unfortunately, the most used, quoted, and cited. The pressure to produce, the availability of seemingly credible industry information, the repetition by gatekeepers and others of that information, and more is where zombie statistics come into play.

Zombie Rising: Brainless Acceptance

Zombie statistics is a playful term I initially heard used in the podcast, Maintenance Phase. If you’re interested in an analysis of the many wellness and weight loss fads, etc., you might enjoy listening to the hosts. In the zombie episode, the podcast’s hosts don’t really define what zombie statistics are except to note that they are the same numbers that are constantly thrown out to support narratives, such as “three out of every five Americans are overweight” or that obesity in the U.S. costs “$90 billion a year.” Few, from government agencies to industry experts, question these numbers.

According to the hosts, the big problem (and a key attribute to being a zombie statistic) is that those numbers are untrue. The hosts get into the reasons why on their podcast. According to them, despite the debunking and non-credible origins, zombie statistics have gained traction and are repeatedly mentioned in media and journals. They are repeated, despite their falsity, taking on a life of their own through that repetition.

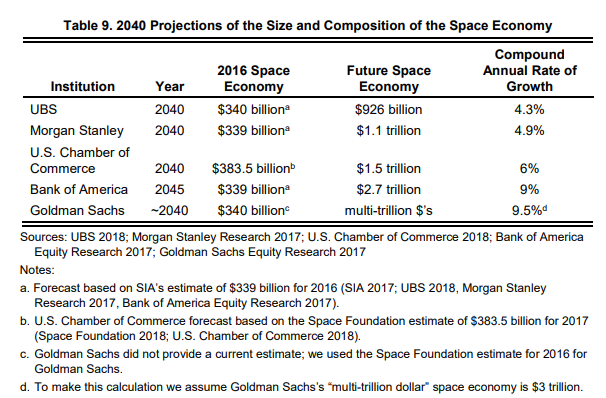

The global space industry suffers from zombie statistics, too. One zombie statistic, for example, is also a forecast (so, zombie augury statistics?)--the trillion-dollar space economy. That number, one trillion, is usually associated with a year (2040). That forecast also appears to have originated with one particular company–Morgan Stanley–although others have offered more or less optimistic projections at nearly the same time. The table below shows many of the projections, courtesy of researchers at the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA).

There was a lot of excitement coming from people who should have known better when Morgan Stanley first announced its zombie statistic. The forecast showed that the space industry would make it big one day. Moreover, the space industry’s products and services would make plenty of risk-takers rich. It’s a good news story that buoys ideas to invest in the industry against all common sense. After all, investing in space is investing in humanity’s future (albeit a tiny percentage of humanity). Plus, there are lots of rockets.

Zombie Dissection

One probable reason why Morgan Stanley’s forecast keeps getting reanimated (aside from its PR efforts) is it sounds just “big” enough to interest people and is simple enough to remember. For future hype masters (and “Institutions”), there’s a lesson there. Conversely, Goldman Sachs’ “multi-trillion $’s” verges on uselessness for those seeking to support fictionalized business strategies. If an institution is going to throw out numbers for the public and investors to latch onto, then it should be a large and round number (per Dogbert).

Another aspect that makes the Morgan Stanley forecast a zombie is that it is rather uninspired, as evidenced by the modest compound annual growth rate IDA helpfully provides. And yet, the company promotes it as a big deal. However, if an industry is gang-busters, it should experience much higher than ~5% annual growth. But it appears that Morgan Stanley is relying on people’s inability to do the math, hyping up the space industry as the next trillion-dollar industry.

One other reason for the forecast’s zombie-ness, though, is that it strays (as others do) from “pure” space activity. From IDA about the origins of Morgan Stanley’s forecast:

“Over three-quarters of this total is projected to be from an increase in broadband internet demand and the accompanying demand for ground equipment, as well as the secondary effects of increased broadband internet on ecommerce, online advertising, and social media revenues (Figure 6).”

Based on IDA’s explanation, those secondary effects Morgan Stanley’s forecast relies upon aren’t generated by the global space economy. Those increased effects (ecommerce, online advertising, and social media) could just as easily be explained by a new terrestrial internet service provider coming online in an area and not space-specific broadband systems. The purposeful blending of revenue sources from non-space-specific services is done for one reason: to make the forecast look bigger.

But the main reason for the zombie characteristic is that people mindlessly use that statistic over and over and over again. Each time, the zombie rises, sometimes even in headlines. It’s a convenient zombie to reanimate, with some businesses sewing new parts on the zombie to make it appear more real, even as it stinks a little more.

Zombie Horde

Other zombie statistics in the space industry show up in other ways—SpaceX’s low dollar-per-kilogram launch costs, for example. To be clear, there’s no arguing that the company offers extremely low pricing for launching spacecraft to orbit. But, also, the company isn’t responsible for people pointing to its pricing as the level at which all launch companies price their rockets.

However, people do use SpaceX’s pricing as evidence that the entire industry is coming down to SpaceX’s level. It hasn’t. It especially hasn’t in the smallsat launch sector. And yet, nearly every week, there’s a story that alludes to the historically low costs of space industry launches, using the zombie launch price statistic from SpaceX to support that assertion. Interestingly, there’s usually no number cited in those stories to support that particular zombie, but, like eating a plate of spoiled oysters earlier in the day, nothing prevents its inevitable rise.

Those are but a few examples of zombie statistics in the space industry. They get used not just for feel-good industry stories but are repeated to support many other industry claims. Worse, their repetition all but assures their use by students–those passionate enough about the industry to study it. They build their arguments and business cases on sandy foundations because they encounter zombie statistics over and over in their research. Why should they question data provenance when the people whose job it is to do so not only don’t but instead actively keep reanimating them?

Surely, there are other space zombie statistics out there. If you have a list, seeing it in the comments or on social media would be fun and fantastic. Who knows–it might generate another article.

Comments ()