Seeing Infrared, Part 1: Large, Big, Fat, Juicy Targets

The DoD’s Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) awarded Lockheed Martin an infrared satellite manufacturing contract last week. While I was tempted to title this “Lessons Not Learned, Part 3,” there’s more to write about than SMC’s culture of risk aversion through profligate spending (an analysis of SMC’s issues here). Here are my observations:

- NGOPIR satellites are too expensive

- The NGOPIR satellites will remain tempting targets

- The missions for NGOPIR satellites will not deviate much from SBIRS current mission

- NGOPIR satellites will be employed similarly to SBIRS

- NGOPIR satellites don’t respond to current DoD concerns

- NGOPIR satellites’ capability and technology will be evolutionary from that of SBIRS

- NGOPIR satellites will need a new ground system

This part of the analysis will cover the first two observations (bolded). Of course, all this analysis assumes that early missile warning from space is essential.

Too Expensive and Too Few=Juicy Targets

From a 2017 SpaceNews article:

“One problem that needs fixing is how the Pentagon procures satellites, Hyten said. The Air Force spends too much money and time developing large satellites that make attractive targets, he said. “We have huge capacity in space right now that pretty much overwhelms anybody.” But he worries that the military may not be able to defend those assets.”

The Hyten quoted is U.S. Air Force General John Hyten. He had been wrestling with the persistent problems within the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) acquisitions processes for acquiring military space systems. The satellites the DoD’s SMC acquired were too few and too pricey. From the same article:

“And, as a combatant commander, I won’t support the development any further of large, big, fat, juicy targets. I won’t support that,” he insisted. “We are going to go down a different path. And we have to go down that path quickly.”

He’s referring to U.S. military satellites costing billions of taxpayer dollars that took decades to manufacture and deploy. Those satellites are not easily nor quickly replaced if destroyed, either because of an anomaly or an enemy action. Hyten surely had in mind national security space programs such as the Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS), which lasted over two decades, didn’t field capabilities the program was initially supposed to, and still cost taxpayers billions.

By 2018--22 years after the program’s initiation--each geosynchronous SBIRS satellite’s costs were estimated at $1.7 billion each (except for the very last two, which cost around $1.4 billion each). The SBIRS satellite manufacturer, Lockheed Martin, said the lower costs were through efficiencies gained in using a standard satellite bus (the LM2100) and the government lifting of some red tape. Still, in 2013 Boeing started manufacturing a relatively “high-tech” high-throughput communications satellite for Viasat for ~$625 million. Is the extra $1.1 billion spent on each SBIRS satellite just for infrared sensors?

But in 2018, and now in 2021, SMC shrugged, ignored Hyten, and pushed billions more towards Lockheed Martin for the Next Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (NGOPIR?) system. Between the development contract issued in 2018 ($2.9 billion) and the manufacturing contract for three NGOPIR satellites given to Lockheed last week ($4.9 billion), the cost for just the “GEO'' portion of the military infrared system will be nearly $8 billion. That’s an astonishing $2.7 billion per satellite.

To put the satellite’s high cost into context: a single NGOPIR satellite costs a little more than a quarter of the estimate for funding Starlink’s (~$10 billion) or at least half of OneWeb’s satellite constellation costs ($5.5 billion). The money for one NGOPIR satellite would pay for nearly 11,000 Starlink satellites, or 270 (edit—actually 2,700—math is hard) OneWeb satellites.

Those commercial low Earth orbit broadband constellations have satellites using high-bandwidth communications terminals--some even have collision avoidance systems. The common components OneWeb and Starlink satellites use are likely more capable than similar components on an NGOPIR satellite. Their deployment numbers make these LEO broadband constellations inherently more resilient and redundant. A satellite failure in these constellations is seen as inevitable, part of the business plan, with little impact on customers. NGOPIR, on the other hand, doesn’t account for this type of failure.

Lessons Not Learned, Part Trois

Instead of acknowledging fundamental changes occurring in the battlespace and the U.S. space sector, SMC literally doubled down on “large, big, fat, juicy targets.” As you’ll see, considering the premium, the satellites themselves won’t have changed much. And the planned missions for these satellites will not be deviating from SBIRS’ current missions, either. Whatever is “next generation” about these satellites, the spending, acquisitions program, and satellite manufacturing are displaying hallmarks of “previous generation” processes.

Justifications for higher costs were provided in a C4ISRnet interview:

“With the preliminary design review complete, the program can move forward with “the build and integration of engineering design units for critical subsystems and procurement of critical long-lead flight hardware for a 2025 first Space Vehicle delivery,” said Col. Ricky Hunt, the space segment program manager for Next Gen OPIR. "These [units] are key enablers to demonstrate subsystem capabilities and exercise key integration activities that will burn down program risk before the space flight hardware is delivered.”

Notice how everything is “critical” and that SMC requires Lockheed to “burn down” risk? Based on the near cost-doubling from SBIRS to NGOPIR satellites, it appears that the red tape is back. Simultaneously, SMC expects delivery of the first NGOPIR satellite in about four years, with the full constellation deployed in 2029 (still not fast). On the other hand, I am extremely confident in Lockheed’s ability to exceed this deadline, as the company has never met an initial DoD deadline it didn’t ignore.

Aside from the red tape, what is it that could make NGOPIR satellites so expensive? What is so special about them that these satellites must cost as much as they do (and that the DoD is willing to shell out the cash to do so)?

Let’s start with these infrared satellites’ fundamental nature: they are Earth-observing and remote sensing satellites. They share some traits with weather satellites, insofar as they peer at about ⅓ of the Earth’s surface from geosynchronous orbit (GEO)--except with infrared sensors. These satellites use sensors designed to detect infrared energy--specifically energy profiles associated with missile launches. Although, as you’ll see in the analysis later in the week, detecting and tracking infrared energy, whether emitted or reflected, can be useful to the DoD in other ways. Essentially, though, the GEO versions of these satellites stare at the Earth’s surface 24/7, gathering data and passing the collected data to a ground station in its view--24/7.

While at high altitude, that orbit is a reasonably simple altitude for aggressive nations with native launch capability to reach. Any country that has launched communications satellites to GEO can launch weapons to GEO. The fact that only three NGOPIR satellites will be in GEO makes the idea of taking out those satellites very appealing. It’s also doubtful that even if NGOPIR satellites had the agility to move out of harm’s way, they would be able to conduct their mission simultaneously. This type of disruption would still be a win for an adversary.

Of course, there is the more devious way--penetrating and using enemy networks to deny the USSF the use of an NGOPIR satellite. If an enemy is smart and has the means, taking these satellites out in a way that causes some doubt about who did it (i.e., hijacking the satellite) would be ideal. In other words, ASAT rockets may not even be necessary. Both of these options are the most obvious ways of diminishing the U.S.’ early warning capability.

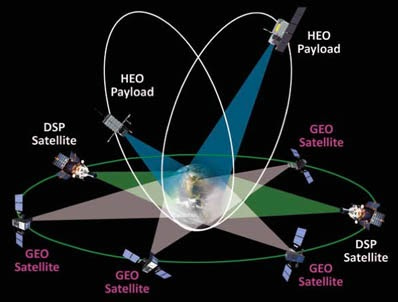

Merely three operational NGOPIR satellites represent a lack of system redundancy/resiliency. It will take Lockheed at least eight years to get all three satellites launched, making that lack of resiliency apparent. Frankly, if you look at how the USSF operates current SBIRS and older DSP satellites (below), you’ll see some overlap (primarily using DSP satellites that are decades old). But you can see that an adversary only needs to take out one satellite (maybe two) to diminish U.S. early warning capability significantly.

Image from AFSPC.af.mil

If an NGOPIR satellite became non-operational because of enemy activity, the USSF can’t afford to wait at least three years to get a new NGOPIR satellite in orbit. The enemy has no reason to provide the U.S. military any time to respond. The new NGOPIR contract does nothing to change this calculus. Was nothing learned from SBIRS?

The next part of the analysis (later in the week) will show how:

- The missions for NGOPIR satellites will not deviate much from SBIRS current mission

- NGOPIR satellites will be employed similarly to SBIRS

- NGOPIR satellites don’t respond to current DoD concerns

- NGOPIR satellites’ capability and technology will be evolutionary from that of SBIRS

- NGOPIR satellites will need a new ground system

Comments ()