Pretense of Competition: U.S. National Security Space Launch

Breaking Defense released a story last week of some U.S. House members attempting to keep things as they are with the Space Force’s National Security Space Launch (NSSL) program. The members are circulating a draft letter that Breaking Defense’s sources say the United Launch Alliance (ULA) drafted. What that letter proposes, especially if ULA is truly its author, is unsurprising but frustrating.

“Buying Down” Risk Through Exclusion

Essentially, the letter encourages the Space Force to adhere to NSSL’s restrictions for selecting potential launch services instead of amending NSSL to consider newer, possibly less expensive, competitors. According to Breaking Defense, sticking with current restrictions effectively keeps large and small U.S. launch providers (except for ULA and SpaceX) from bidding on Department of Defense (DoD) launch contracts. In other words, the NSSL works just great for two U.S. launch companies, especially if ULA happens to be one of those.

For those wondering what NSSL is supposed to accomplish, its purpose can be summarized in two words: risk mitigation. It’s an attempt to lower the risk somehow, however laughably remote it may seem, that one of the U.S. military services will have a satellite ready but no way to launch it. The typical nonsensical DoD bureaucratois describes the NSSL’s reasons for being this way:

“The NSSL program is designed to continue to procure affordable National Security Space launch services, maintain assured access to space, and ensure mission success with viable domestic launch service providers. The program is driven to provide launch flexibility that meets warfighter needs while leveraging the robust U.S. commercial launch industry, which has grown significantly during the past five to seven years.”

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) interpreted that to mean: “mission success, innovative mission assurance, transitioning to new launch vehicles, and assured access for future space architectures.” Note the similarities of that interpretation to the following program description (also from CRS):

“The purpose of EELV was to provide the United States affordable, reliable, and assured access to space with two families of space launch vehicles.”

A Program by Any Other Name…

No mistake, that description is for the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program (EELV), but NSSL is EELV–only it allows for reusable launch vehicles, too (the “new launch vehicles” part). Coming back to the point: risk mitigation is a program focus anytime the words such as assured, ensured, reliable, etc., are used to describe its intent (although I am unfamiliar with the term “innovative mission assurance”). At the time of EELV’s inception, the DoD had genuine worries about launch costs, launch vehicle reliability, and ultimately, whether there would be “made in the USA” launch vehicles available to launch U.S. military satellites. The big problem, which doesn’t bode well for NSSL, is that EELV didn’t work to alleviate those concerns.

Admittedly, the word affordable does require some context–as in just asking: “Affordable for who?” But with that caveat out of the way, EELV didn’t keep launch costs affordable. It went through at least two Nunn-McCurdy breaches (indicators that EELV program costs were out of control). The two competing launch companies eventually created a single launch company–ULA (albeit with two different rocket families)--resulting in a monopoly. To be fair, ULA launched its rockets reliably. But for the DoD, the program only met one out of three of its goals, failing the very low bar set by the Meatloaf standard acceptance ratio.

However, that lopsided result didn’t change the way the DoD felt about these programs, pouring on and out its support behind them. So it naturally renamed EELV, possibly hoping no one would notice that NSSL’s goals are remarkably similar to its predecessor’s.

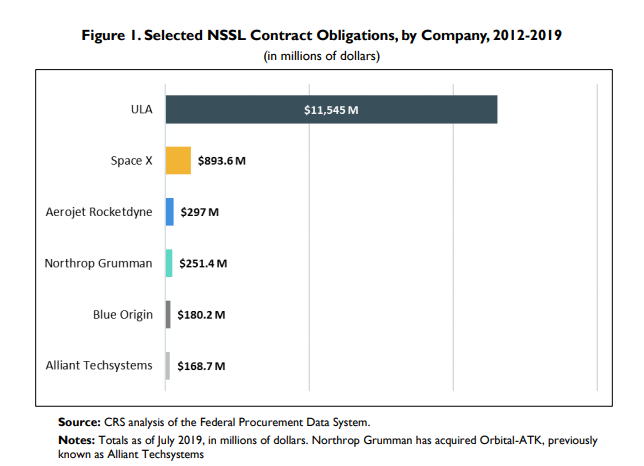

NSSL is also attractive to U.S. launch companies because it doles out significant monetary amounts for their launch services (as EELV did). The DoD routinely pays more for launch services than commercial companies do. As much as some advocates would like to think otherwise, inflated U.S. military launch contracts provide significant support to U.S. launch companies–because the DoD overpays for those services. NSSL is what’s keeping the lights on in ULA’s storage facility as its Vulcan rocket bodies wait for Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine. A CRS chart shows why NSSL is attractive (and why ULA is surviving):

Limiting Flexibility

As noted in the report, only SpaceX’s and ULA’s rockets are NSS-certified to the standards that the House members are pushing the Space Force to keep in play. But, of course, the primary member pushing it, Representative Lamborn, just happens to have ULA in his Colorado backyard. However, he is only a politician, so his push leans heavily on the trust he seems to be placing in ULA’s stated position.

That ULA appears to be the instigator of this idea is also not surprising, not just because it stands to be the primary beneficiary of the program (SpaceX seems always to get a smaller share of NSSL-apportioned contracts). The company’s CEO, Tory Bruno, has consistently maintained that the NSSL “market” can only support two launch companies (and of course, ULA would be one of those two). That misguided contention would be true if a commercial market is defined as being free from those pesky concepts of competition, supply, and demand. However, as a local grocery store easily demonstrates (and as argued before)–the NSSL program is not a market.

However, there is another very good reason why the Space Force should ignore Lamborn’s and ULA’s entreaties and open up NSSL to more competitors–it may end up narrowing down NSS-certified rockets to that of one company–SpaceX. It’s already somewhat true with ULA’s current situation, in which all operational rockets in its inventory are spoken for (the analysis of this problem is here). That possibility is based on the fact that ULA must still certify its Vulcan rocket. ULA wrangled the number of flights required for certification down from three to two. There is a chance, though, that the Vulcan fails during one of those launches. It might be a small chance, but the consequences downgrade the DoD’s ability to use rockets from two different companies.

NSSL’s purpose is risk mitigation. This is why, at least on the surface, it’s a little puzzling for the DoD to dole out contracts for a rocket that doesn’t exist under the program. Looking a little deeper, however, shows that the DoD doesn’t have much of a choice and that perhaps those contract awards are based on hope.

It’s hoping that ULA’s newest rocket will function well right off the launch pad, because if it doesn’t, SpaceX is the only alternative. No other U.S. company has an operational rocket that compares to an Atlas V, Delta IV, or Falcon 9. The U.S. military has probably watched Blue Origin’s New Glenn development with disappointment, as that would have at least provided some kind of alternative. But the development of that rocket is impacting ULA’s Vulcan efforts, too. And that impact must be dismaying to the DoD. Despite the lack of a real rocket, the DoD still gives ULA the larger awards.

To heed Lamborn’s and ULA’s call to stay the course in a program that historically didn’t work isn’t smart. To keep up the pretense that those program requirements somehow create a competitive market for two commercial companies is silly–especially when contract awards are so lopsided. And to remain with two NSS-certified rocket companies takes away the DoD’s flexibility in meeting the true reason for launching satellites: supporting the warfighter. To be fair, some in the DoD do believe that more competitors are better. Despite that, others would love the DoD to conduct business as usual, not growing a commercially vibrant launch sector, but keeping it static.

It may be that ULA manages to keep its promise that Vulcan will be certified someday, but why take away the military’s flexibility to support its warriors based on that hope?

Comments ()