Potential U.S. Space Force Changes

Several years ago, I analyzed the missions the proposed United States Space Force (USSF) was supposed to inherit from the United States Air Force (USAF) and others. It was then, as it is now, primarily a military service that provides support to the combat services, such as the Army, Navy, and the USAF.

At the time, this new(ish) organization, the Space Development Agency, was beginning to publish plans for a space architecture. I don’t believe I was the only person skeptical about yet ANOTHER organization that said it would change U.S. military space acquisitions AND bring about spacecraft that would fundamentally change how the USSF conducts space operations.

But the agency is doing both, whether the USSF realizes it or not. More on that bit later.

Space Service Similarities

At the beginning of this month, I decided to provide an update to the charts and the observations about the service I made in that several-year-old article. And, frankly, I provided updated observations of the USSF in the analysis that followed that note. The upshot of the analysis is that the Space Force remains a support service. The architecture the SDA is implementing will only emphasize that support role in the short term. Again, more on that later.

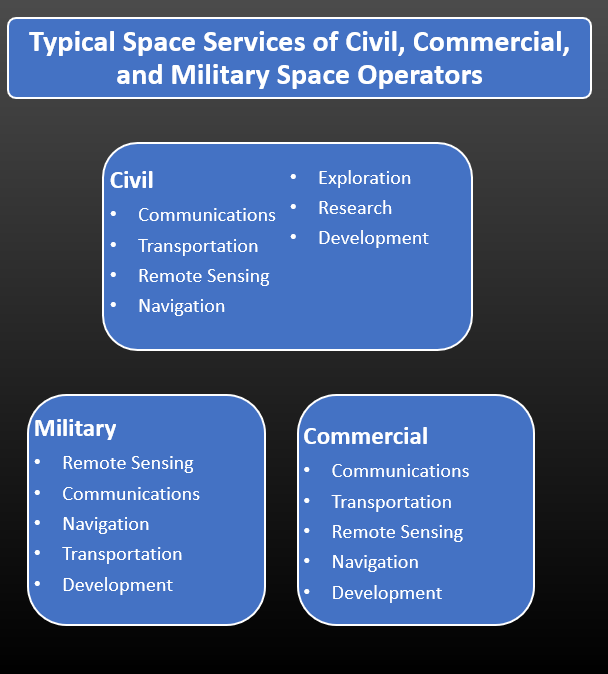

The USSF’s missions and assets make its support focus clear. In the context of the other types of space operators in civil and commercial sectors, the Space Force's services are not much different.

Military space operations provide services similar to civil and commercial counterparts in many ways. In some ways, it provides a different type of service, such as missile warning or tracking in remote sensing. That makes sense, as those missions have few commercial applications. In other ways, U.S. military space lags, such as communications, particularly with LEO data networks or, possibly, in remote sensing regarding synthetic aperture radar constellations.

What is not evident, based on my admittedly old knowledge, is that the U.S. military is currently relying on old systems, which means a lot more people, military, contractor, and civilian, are involved behind the scenes. These are ancient systems–ancient, as in relying on UNIX or an even more arcane operating system for spacecraft commands.

They might be relying on contractor-provided one-off operating systems, which isn’t great. And that’s a problem because U.S. military operators get trained in the quirks of those systems, from troubleshooting to commanding. When they leave the service, they’ll understand space fundamentals but will be behind in the commercial companies' technology.

The Challenge of Legacy Systems

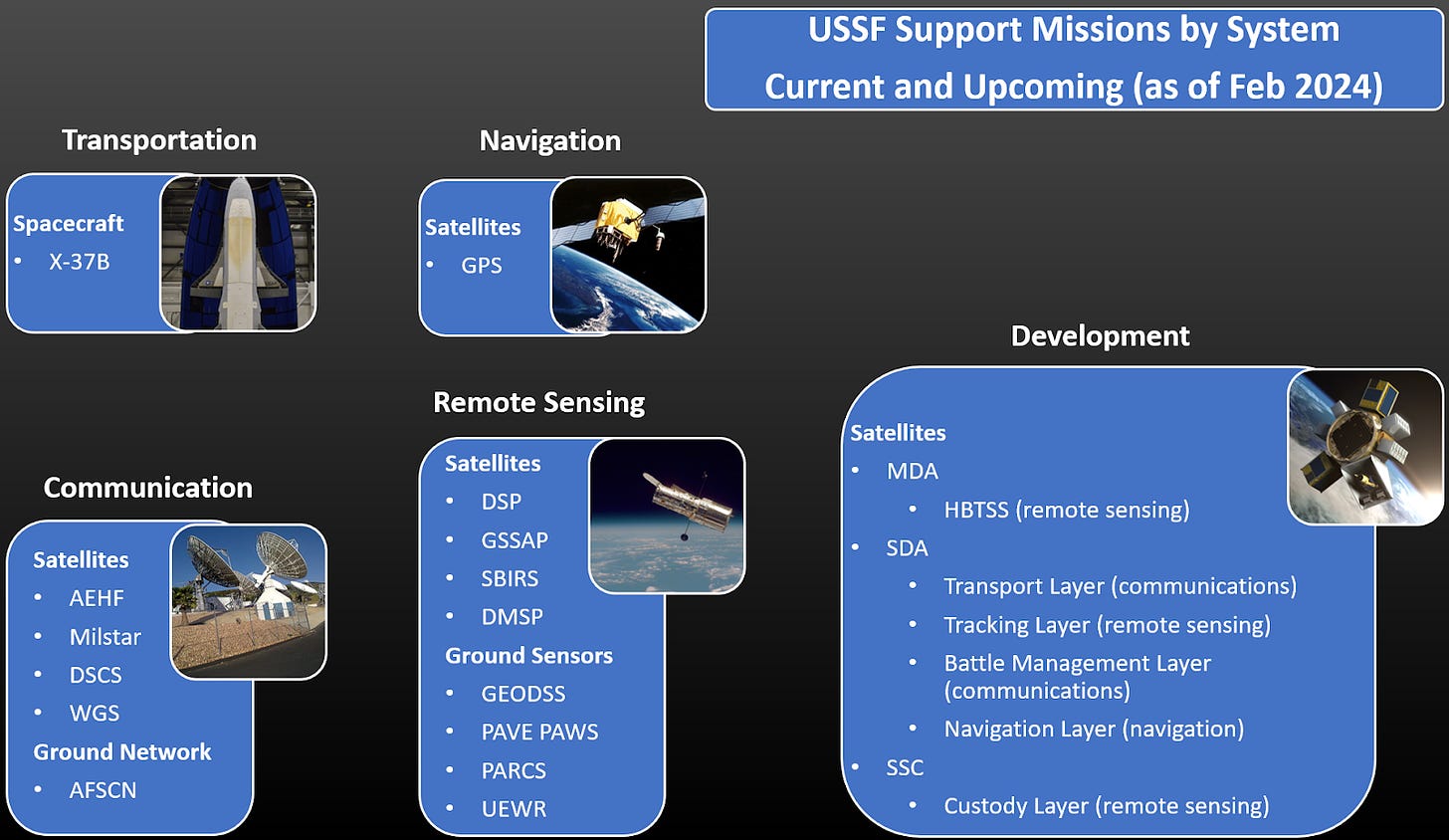

The Space Force lists those systems in its Fact Sheets. There are other support services it provides, but these are apparently what the USSF deems important enough to rate an official web page. Here is an updated chart based on those systems, showing how they fit into the space service categories.

For those wondering what the acronyms mean, the USSF’s Fact Sheets will help. Again, those are old systems, a few of which have been around for decades. That alone is an excellent reason why the USSF turns to commercial operators and their sleeker operations, updated operating systems, and updated tech.

Four service categories are infrastructure: communication, development, navigation, and transportation. For those wondering about launch, well, the USSF isn’t the one doing the launching–it supports launches conducted by commercial operators. So, regarding operating actual transportation, the X-37B is the only vehicle the public is privy to that the USSF operates.

Development aggregates the other service categories, as MDA, SDA, and SSC are all working on technology that will eventually transfer to communication, navigation, etc. However, the development section portends a future in which the systems those groups work on will be interoperable. That is a concept the USSF has yet to train for.

As noted earlier, the older systems require specific training, which can take many months, depending on the system. Military operators become “certified” on a space system such as SBIRs/DSP, GSSAP, GPS, etc. Once certified, they are considered the nascent experts for their systems. However, not one system is designed to operate with the other (some systems rely on space communications). The USSF doesn’t have interoperable space systems.

Deltas of Excellence and the PWSA

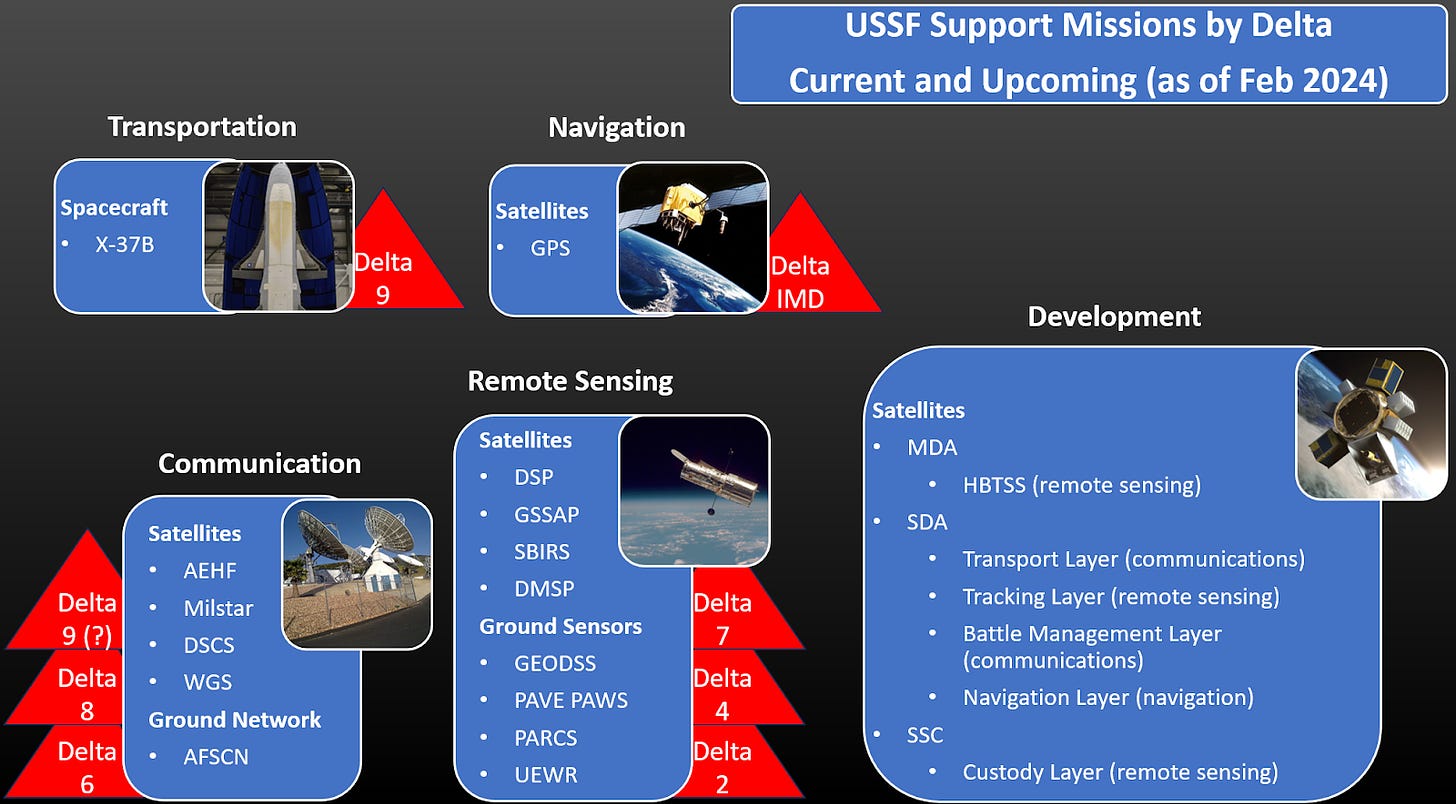

Several efforts have been made to fuse the results from these systems, but the attempts are akin to fitting square pegs in round holes. The operators themselves generally focus on commanding and monitoring their systems. Below is my attempt to capture the various units (the USSF calls them “deltas”) responsible for the different Space Force systems.

Linking those relationships is a little more challenging than it should be. The USSF uses descriptive and deceptive language for EVERY SINGLE DELTA to make them all seem like space badasses. Of course, what they are doing is very important, and each one is special.

But, my goodness, here’s an example with Delta 9 (sorry, guys), which purports to implement something that sounds exciting: Orbital Warfare. Its mission is: To protect & defend U.S. & Allied interests in space through orbital warfare operations. That sounds cool! But what does it do?

It is responsible for running the X-37B reusable spacecraft, which means the delta is in on deploying/retrieving specific secretive payloads in orbit. However, there aren’t many X-37Bs. One USSF article noted that a Delta 9 squadron is responsible for the “characterization of threats ops to protect and defend our space capabilities.” Based on the context, that statement has a cyber-warfare flavor, but if so, what does that responsibility mean?

What is the USSF’s definition of orbital warfare, anyway? Searching for that word combination yielded no official definition. Perhaps it isn’t officially defined–odd for a service that purports to have military space expertise. A 2020 paper suggests the service hasn’t defined it and attempts to define it in a note (page 3):

“As there currently exists no official DOD definition for “orbital warfare,” I have defined the term for the purposes of this paper as “Warfare conducted whereby the attack vector originates in the space domain.””

It’s a good enough definition. Based on that definition, however, it would exclude cyber-warfare and orbital cargo services. Enough of the rabbit hole…readers hopefully get the idea.

Back to the near future of Space Force operations, the PWSA. The charts above show that the PWSA’s systems will only reinforce the USSF’s support role. More importantly, however, the systems will be updated and (hopefully) more capable. They will require a space operator mindset different from the USSF’s deltas of excellence.

SDA’s Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) looks highly interoperable. The systems have to be for it to work, meaning that space operators for those systems will need to interact with each other more than they’ve ever done. The operators in charge of the Transport Layer (the communications network) must work alongside the other operators for the other layers.

They will all interact often and quickly; otherwise, the system will fail. They probably won’t have to select a channel to communicate with someone hundreds to thousands of miles away to coordinate messages and data. That person will already be on the operations floor with them. It will be much different than what the USAF or USSF has done with space operations.

PWSA and Other Possible Futures

But is the USSF ready for that? For example, it’s unclear whether its classification guidelines that protect the current USSF space systems and keep them stovepiped will be prepared for that kind of interoperability. The answer to that challenge is the examples of space systems and mission cooperation in other organizations.

The other challenge would be the USSF’s force transition from legacy space operations to the PWSA. Will the USSF be required to maintain a stream of candidates to operate older systems (which could create some morale issues) even as it tries to step into the future? Or will it become as aggressive in its operator training as the SDA in spacecraft production?

Of course, none of this starts moving the USSF away from a support role. Aside from the electromagnetic warfare group, which it doesn’t list on its Fact Sheets, are there other missions that could move it away?

What if it bought a fleet of Falcon 9 reusable rockets and trained mechanics and others to launch and land them safely and successfully each time? That’s closer to what the USAF does with its fighters, bombers, and transports than anything else in the USSF’s inventory right now. It would allow the USSF to launch at will, which it really can’t when relying on commercial launch services. That admittedly unlikely scenario would still keep it in a support role.

Even without considering those outlandish thoughts, the PWSA will likely make for a more comprehensive and formidable system of systems than what the USSF operates currently. Its space operators will work more jointly in that architecture than now. That could make a positive difference for their compatriots on the battlefield.

If you liked this article (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), any donations are appreciated. For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU!!

Comments ()