National Security Space Launch: ULA and Trust Issues

During the second half of October 2024, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) announced it had awarded two launch contracts to SpaceX. One pays SpaceX to conduct seven Space Development Agency (SDA) launches, while the second is for two National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) launches using SpaceX’s launch service. The total value for the two contracts is $733.5 million, or about $81.5 million per launch, which, for the DoD, is relatively inexpensive.

The Omission

The oddest part of the announcement was the omission of mentioning at least one of the other two companies that were also competing for the contracts–Blue Origin and the United Launch Alliance (ULA). No one should be surprised that the DoD didn’t select Blue Origin. The company doesn’t have a working orbital rocket yet. A risk-averse military isn’t going to choose a company that hasn’t demonstrated its core competency (aside from chasing many, many contracts) at least once. So, the DoD not selecting Blue Origin is only odd because it exhibited common sense to determine that Blue Origin wouldn’t get the contracts.

However, the really odd part of the announcement was that ULA did not get any launch contract award in that announcement. Bupkis. Nada.

In the past, ULA has stepped out of award processes if it thinks it can’t compete. But it is unusual for the military government customer not to select it if ULA throws a hat into the ring. Usually, the DoD can be counted on not only awarding ULA a few launch contracts but also giving it the majority of launches. SpaceX usually drew the short straw whenever ULA vied for the same awards, but not this time. SpaceX got all the contracts.

What changed? Trust–the loss of it.

Hard to Win, Easy to Lose

Around the middle of 2024, I finished and posted a revised gap analysis of ULA. The launch services landscape had changed significantly enough that it was a worthwhile exercise. After I posted that analysis, I then posted this observation:

Maybe the most significant observation between the two gap analyses is the DoD’s apparent withdrawal of trust in ULA’s ability to conduct launches reliably. In this case, “reliably” refers to the company’s ability to launch when the government needs it to.

It’s the whole “US Government has doubts about supporting ULA” thing. And that loss of trust is a BIG DEAL for ULA. As noted earlier, the company relied on the DoD’s trust to win larger launch contracts, extract more money per launch, etc.--despite not having launched Vulcan once. ULA’s first Vulcan launch was conducted behind schedule (which put DoD launches behind schedule). The company still seems to make uncertain statements surrounding future launch cadence, likely because it doesn’t know if its engine supplier can keep up.

The part of the analysis that prompted my observation was whether ULA’s customers were satisfied (or not). I noted that the DoD “has doubts about supporting ULA” and provided the following data for why:

- Late in getting Vulcan certified for National Security Space Launch

- DoD levying late launch penalties

- Dependence on Blue Origin for engines

- Decreased launch cadence inadequate to fulfill NSSL contract obligations

- Large commercial commitment (Kuiper) impacts NSSL contract

- Possible acquisition by Blue Origin (an unproven launch operator)

Note that the above data were changes that occurred three years before that revision. My original analysis noted that its government customers didn’t like the company’s use of Russian-made engines and occasionally made noises about high launch costs. However, they did like ULA’s reliability of service and launch vehicles. So, the loss of trust is a significant shift in the customer’s attitude toward and interactions with ULA.

The data from that mid-2024 analysis hasn’t changed. ULA is still working out the kinks with its Vulcan rocket. Those kinks might be why the DoD hasn’t yet certified it for National Security Space Launch, so it’s still late in its certification. ULA still depends on Blue Origin for Vulcan’s engines (which seem, thankfully, reliable). Its launch cadence has decreased quite a bit, it’s still juggling the Kuiper contracts, and its future is still not assured.

The DoD, then, still has reasons not to believe that Vulcan will be ready for NSSL launches. In addition, ULA was horribly optimistic about Vulcan’s projected debut date when it persuaded the DoD to award the company contracts that used Vulcan. Those awards were a public relations risk the DoD didn’t have to take but did. As noted earlier, the DoD usually awarded more launches to ULA than SpaceX. Doing the same thing several times, even though the ULA did not have an operational rocket on hand, is where the bias showed itself to the public.

The DoD will never publicly say it has lost trust in ULA (barring disastrous performance). But actions, especially actions doling out money, speak louder than words.

A Hole in the Hull and Blinding Optimism

In that earlier analysis, I noted that the launch penalties and the government customer’s pointed language used regarding ULA not fulfilling the contract as required were shots across the company’s bow. The latest action of awarding all contracts to SpaceX without divvying them between SpaceX and ULA is a shot into ULA’s hull.

The DoD isn’t going to use ULA’s newest rocket until the company proves it is ready and reliable, especially not for NRO launches. And it doesn’t trust ULA’s Vulcan readiness estimates like it did just two years ago. The U.S. military has likely done a risk analysis, the weighing of which would include very reliable rockets from SpaceX. The result is what we see here. The DoD risks nothing by not choosing ULA. ULA (or its successor) will receive more contracts if Vulcan becomes more reliable. Until then, SpaceX gets its business.

I don’t believe the DoD wants this situation, but I wonder if it’s experiencing a willing and optimistic blindness. It seems to think that its latest National Security Space Launch program is working, relying on various phases to induce companies somehow to build the rockets it needs:

“Industry stepped up to the plate and delivered on this competition. Our innovative dual-lane strategy is enabling a streamlined process from mission acquisition to launch, getting our assets on orbit for our warfighters’ benefit more quickly,” Downs said. “Plus, with the ability to on-ramp new providers and systems annually, we expect to see increasing competition and diversity.”

First, to say that the industry stepped up to the plate and delivered is an interesting interpretation of the contract award results. Sure, three companies vied for the awards. One still needs an operational rocket, and another is still navel-gazing from its last launch. SpaceX is the only one of the three that had any chance at the award. And if it wasn’t the only one seriously contemplated, then the DoD has another problem entirely.

Second, maybe the acquisitions model is streamlined, but it still took a long time for the DoD to make this decision–despite there being one viable choice. These agencies generally know the masses and orbits these rockets will be used for before selection. They might even have already chosen the rocket that fits their criteria (there are few rockets to choose from). How does that get assets to warfighters more quickly?

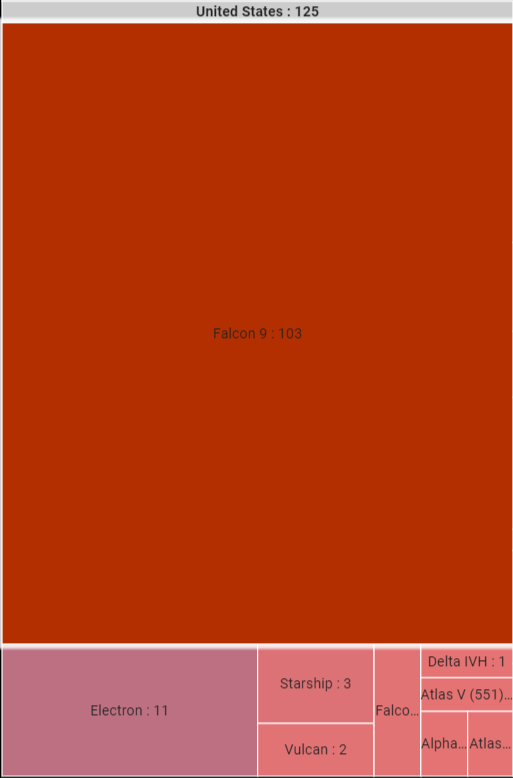

As for anticipating increased competition and diversity in launch, it’s unclear where the speaker is looking (maybe a Magic 8-Ball?). The above treemap shows which launch systems the U.S. companies fielded in 2024. Two are retired, and another is a suborbital prototype, meaning only five orbital launch systems (one is the Vulcan) are available to the DoD.

There are no Falcon 9 competitors, and whatever is coming down the pike (Neutron, Medium Launch Vehicle, New Glenn) is still a lot of smoke and mirrors. Electron and Alpha can only lift smaller payloads than the Falcon 9. Vulcan is getting some duct tape treatment and must work on upping its launch cadence.

Still, the DoD's delusions about what it does for the launch industry (innovation, increased competition, and diversity) keep it from becoming a reality. The DoD needs to look at the industry in a clear-eyed, sober way to achieve the launch system diversity and redundancy it needs to ensure its space missions are launched whenever they need to. Its latest NSSL program didn’t cause ULA to build Vulcan–that was SpaceX. The latest SpaceX awards demonstrate that NSSL hasn’t increased competition or diversity, with little to none expected in the future.

Despite this process, the DoD finds itself relying on a single launch provider for national security space launches yet again. Only this time, it’s not ULA but SpaceX. At $81.5 million per launch, it’s not a bad deal for the DoD, but it doesn’t eliminate its dependency on a single launch provider.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), please share it. I also appreciate any donations (I like taking my family out every now and then). For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU from me and my family!!

Either or neither, please feel free to share this post!

Comments ()