Kuiper: Another Satellite Manufacturing Juggernaut?

A few reminders.

- I appreciate donations or subscriptions. They help keep things running here. If you are reading this or any of my other articles, then maybe consider donating. The link is at the bottom.

- There will be no analysis next week as I'm taking my Labor Day holiday then. Sometimes, it's nice not to labor.

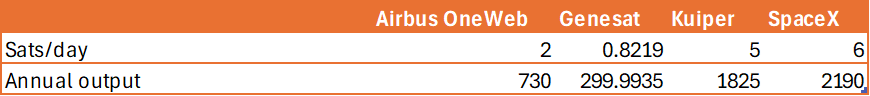

Amazon’s Kuiper posted a press release in June of 2024 that the company’s factory can manufacture five satellites daily (at peak). That’s up from its initial four satellites per day guesstimate in late 2022. That’s more than the two satellites per day from Airbus’ OneWeb facility in Florida and one shy of SpaceX’s advertised daily Starlink satellite production (six). Considering that Starlink has essentially quadrupled in mass since its introduction, the fact that SpaceX has increased its daily Starlink output since then is impressive.

Satellites in Washington

If Kuiper reaches that peak, its satellite output numbers will further consolidate Washington state’s Puget Sound region as the world's satellite mass manufacturing capital. SpaceX’s Starlink manufacturing facilities already made it so. Those two companies, Amazon and SpaceX, have the capability to build slightly more than 4,000 satellites per year (at least, according to them). While there have been many other advertisements for satellite mass manufacturing, mainly from China, I don’t believe any other region or nation hosts that capability.

That’s just wild!

Except, there’s that word–peak. It’s a squishy word commonly used in press releases to highlight a particular aspect of a product, such as speakers (wattage, RMS), chipset speeds, broadband capability, etc. It usually indicates that while a technology can achieve that peak, it won’t usually be able to maintain it (otherwise, it’d be a plateau). Its usage of the word peak makes it clear that Amazon believes Kuipersats can’t be produced at five satellites per day for a year. So perhaps its four-per-day estimate is a more realistic indicator of general everyday production instead of peak.

Mass-Manufacturing Satellites

Still, playing with the higher number–five per day–is fun, which is why I will be using it for the remainder of this piece. Five satellites per day every day of a year totals 1,825 satellites (1,460 satellites at four per day). That annual production estimate tells us that within two years, Kuiper will have manufactured enough satellites that, if they were to be deployed immediately after manufacture, would exceed 3,236 satellites. That number is significant because that’s the total number of satellites that Kuiper told the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) it would be deploying–by 2029.

Thanks to Kuiper’s information, we know it can build enough Kuipersats to fulfill its FCC obligation. Another question is whether the launch services the company contracted with will be able to launch enough in the time remaining. I already covered that in detail last year.

SpaceX remains the top satellite mass manufacturer, but Kuiper’s release makes it appear as if it comes close. Airbus OneWeb does not, but at least that company still talks about satellite output in XX per day and not one satellite per XX months or years. China’s Shanghai Gesi Aerospace Technology (Genesat) promoted that its factory could produce 300 Qianfan satellites in a year–less than one per day. That output rate indicates that Genesat will take over three years to deploy 1,000 Qianfan satellites.

That’s a lot of satellites, but it’s short of Kuiper’s and Starlink’s estimated annual production. A comparison of the four companies' estimated satellite output so far.

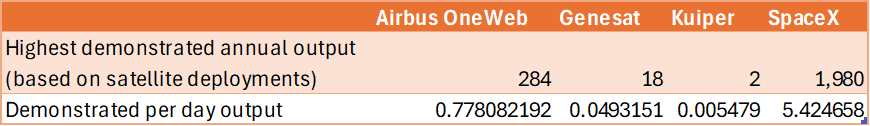

Comparing those estimates with reality can be interesting. The following table counts a company’s highest year of satellite deployments (2021 for OneWeb, 2023 for SpaceX, etc.). To be clear, this isn’t an actual demonstration of how many satellites a factory can produce, merely how many the company had on hand for the year. I then divide that number by the number of days in the year to show how many satellites would need to be manufactured daily to reach the annual number of deployments.

Maybe it’s unfair to use the low initial deployment numbers of Genesat and Kuiper, but it could be that their demonstrated numbers will increase significantly by next year. Also, maybe it’s not surprising that SpaceX comes very close to its advertised annual output number. But it only has come that close in one year–2023. Eight months into 2024, the company has deployed nearly 1,300 Starlink satellites. Based on its monthly 2024 average, it won’t reach its 2023 Starlink deployments, but it will be close.

If Kuiper succeeds in hitting its peak every now and then, then Puget Sound wins the satellite mass manufacturing lottery for at least a few years.

Mass-Manufacturing Impacts?

While it’s good news for the region, Kuiper’s manufacturing may become more of a problem for dedicated small satellite manufacturing companies, such as Hera Systems (to be bought by Redwire), York Space, Terran Orbital (to be bought by Lockheed Martin), etc. SpaceX has already pursued and won military satellite contracts, which those companies rely upon. Amazon has demonstrated that it likes pursuing military contracts as well. Kuiper has explicitly identified its desire to pursue government and military contracts.

None of those smallsat manufacturers bring anything close to the manufacturing capability that Kuiper claims. And if Kuiper’s satellites and busses turn out to be reliable and easy to work with, that becomes more of a problem for those companies (and the ones acquiring them). Companies like Lockheed and Boeing have bought themselves into the smallsat manufacturing business. But was or is it the right move? Did they get bamboozled by small satellite industry hype? To be fair to them, there’s a lot of that going around.

There is nothing wrong with smallsats, but the industry has been trending toward larger buses for at least five years. SpaceX even moved to larger Starlink satellites because the size increase required fewer capability compromises.

As SpaceX and Kuiper seem to be demonstrating, legacy manufacturers such as Lockheed, Boeing, and Northrop should have investigated the ability to build many capable satellites quickly instead of focusing on size. Again, to be fair, the companies they acquired/are acquiring could build satellites faster than their in-house units. But certainly not fast enough to keep up with Airbus OneWeb, much less SpaceX.

SpaceX has already made its mark on what those legacy companies believed to be their turf. Nothing prevents Kuiper from doing the same when it’s ready. The legacy companies, despite their acquisitions, aren’t prepared. It’s not that the legacy companies are in any financial trouble. It’s just that they still seem to be a few steps behind the likes of Kuiper and SpaceX.

Is mass-manufacturing satellites a capability that customers want? Some seem ready to embrace that capability, but others will want to keep legacy companies from fading away from satellite manufacturing. They will likely fall back on manufacturing expensive and unique satellite payloads, and the government customers will buy into those offerings.

SpaceX and Amazon also have excellent reasons for building their satellite manufacturing infrastructure–their space-based internet relay systems. Rocket Lab appears interested in the same sort of business, so it will need to beef up its satellite manufacturing capabilities to support its deployment. In hindsight, it’s a little strange that legacy manufacturers are backed by such broad business portfolios but didn’t seem to use them synergistically. Perhaps their constant work on classified programs is inhibiting that crossflow?

This means that, on a personal level, I’ll have to make an effort to visit these factories (if they’re open to visitors) the next time I’m be-bopping around Seattle. For the wider industry, at least in the U.S., the legacy companies aren’t going anywhere. But they also won’t be as competitive in the government satellite manufacturing business as the newcomers, like Kuiper.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), I appreciate any donations (I like taking my family out every now and then). For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU from me and my family!!

Comments ()