Imbalance of Space Power: Russia and Ukraine

Common History, Different Results

One of the oddest aspects of the Ukrainian-Russian war is the real space power imbalance between the two nations. By the end of April 2022, Russia had 172 operational spacecraft orbiting the Earth. Ukraine…none? Even if that educated guess is incorrect, Ukraine certainly did not have a quarter of Russia’s number. The Russian government has theoretically spent billions of rubles to maintain its space bona fides. It deployed GLONASS (positioning, navigation, and timing—PNT), signals intelligence, communications, Earth observation, and proximity satellites almost yearly.

Ukraine’s space efforts, on the other hand, have been almost non-existent. That observation was prompted by this Atlantic Council report–specifically, the following quote:

“In 2022, Ukraine had no national space capability. Nevertheless, space systems, in the form of third-party commercial and government assets, have played an important role in the Ukrainian war effort.”

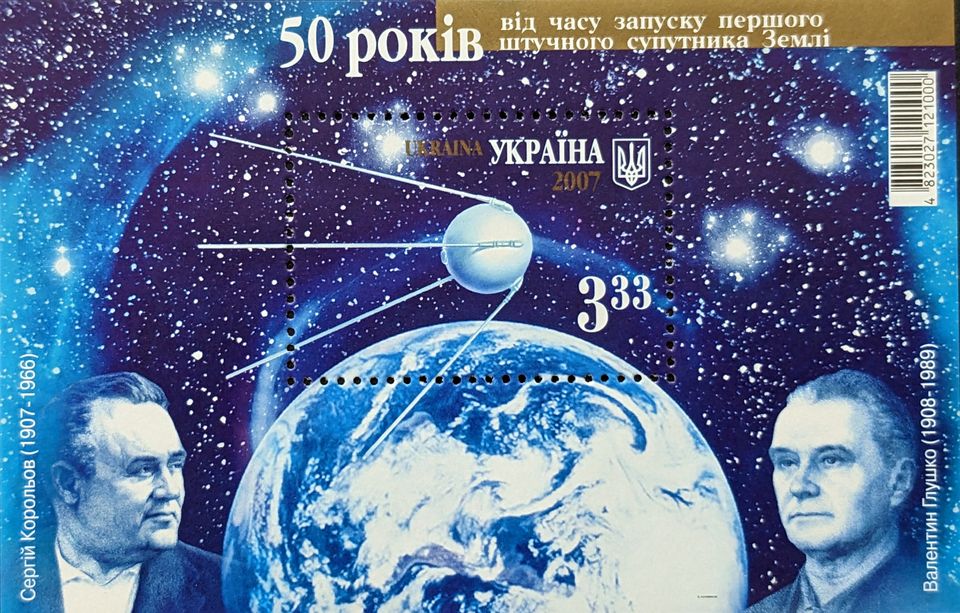

To be fair, Ukraine has faced many distractions that likely rank its space industry efforts at a very low priority. For much of the past decade, the country has been attempting to survive Russian efforts to erase it piecemeal. Complicating Ukraine’s space industry efforts is history, as the nation’s contributions to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) space activities were significant. Much of what made the USSR’s space program a success came from Ukraine. Even the USSR’s father of its space program, Sergei Korolev, was born, raised, and educated in Ukrainian territory. Ukraine was later known for manufacturing rockets, such as the Dnepr and the Zenit (one version of which was SeaLaunch).

As Russian interest and investments in developing in-country rockets grew, its desire to purchase and use Ukrainian-manufactured rockets decreased, another reason for the current state of Ukraine’s space industry. While Russian interest waned, Ukraine manufactured engines for U.S. companies and offered newer rockets to launch in other nations. Most of Ukraine’s space offerings didn’t gain traction.

One recent reason for Ukraine’s absence from the space industry is that Ukraine’s space industrial base is likely in shambles. Russian missiles routinely target cities such as Kyiv, Dnipro, and Kharkiv. While rebuilding its industry is probably desirable, it’s unwise to attempt it with the current situation. Ukraine’s space history, its deteriorating relationship with Russia, and Russia’s annexation attempts resulted in Ukraine not having any national space power at the onset of Russia’s invasion.

Is the Ultimate High Ground not High Enough?

If space is the ultimate high ground, then Ukraine’s lack of space assets indicated a significantly less advantageous position for fending off Russian advances (classic Jedi High Ground thinking). Without government space assets, how would it gain intelligence about where Russian troops were moving? How could it communicate with its troops? Worse for Ukraine, it faced an adversary with many space assets who theoretically knew how to use them.

The U.S. military and politicians drummed up Russia’s military space expertise and capabilities for a few decades. After all, Russia’s military launched all sorts of satellites on various missions nearly every year. Without notice, a few orbiting Russian satellites closed with non-Russian satellites, and the Russian government basically responded to protests with “What are you going to do about it?” U.S. concerns about ground-based lasers and anti-satellite (ASAT) missiles seemed to be borne out as Russia created orbital debris fields from kinetic ASAT testing. The Russian military had fielded GPS and satellite communications jammers before, a capability it unsurprisingly still uses during its stalled invasion of Ukraine–with mixed effectiveness.

And yet, despite all of those technologies, Ukraine exists almost a year later. That same Kyiv Independent article suggested a reason why this might be:

“Russia did not expect to use its satellites during the war because it thought that it could seize Ukraine in a few days,” Kolesnyk said.

It’s hard to buy that suggestion. No military would ever volunteer to give up the use of its space systems on purpose, as no military would ever give up anything that provides its forces an edge on the battlefield. Russia’s military drove tanks and artillery, flew jets and helicopters, and lobbed missiles in the first few days of the invasion. Space assets would surely have been involved in those operations–especially if a cohesive doctrine guided the invasion strategies.

Even if the suggestion was accurate, when it became obvious the war would continue much longer, the Russian military would surely have started using its space systems. Whatever the reason, Russia’s space expertise and technology haven’t come into play very often during the war. Or if they have, the results have been underwhelming.

The Ukrainian military, on the other hand, are using space systems effectively. In that Atlantic Council analysis, one of the conclusions concerning Ukraine’s situation was:

“The war in Ukraine demonstrates that what matters is having access to the products of space systems, not owning the satellites. With the explosion in commercial communications and imaging services, many combatants will have such products. Access will not be universal, however.”

I suggest there’s more that matters than having access (although access is essential). Russian military forces theoretically have access to their space systems’ products but remain on their back feet in Ukraine. Maybe there’s more to space power than how big, expensive, high, and capable a military space asset is. Maybe it’s how you use it and its data.

Battlefield Intelligence, Commercially-Provided

Ukraine has effectively used space against Russia, despite not owning space assets. In addition, Ukraine’s government and military benefitted from increased commercial satellite deployments during the past few years.

Not one week goes by without an image of Ukraine’s battlefields, the destruction of its schools and cities, and more, courtesy of Planet or Maxar or some other Earth observation company. The Ukrainian government has access to those images and possibly the imagery and remote sensing intelligence from allied government sources. There are similar stories concerning Starlink, SpaceX’s LEO broadband constellation, and how it’s providing communications pretty much anywhere Ukraine requires. While the Ukrainian government is paying for those services, that cost is much lower than building and maintaining various satellite fleets.

At least one example shows that Ukraine is going its own way to obtain spacecraft. A Ukrainian charity foundation bought the government a Finnish radar satellite (from ICEYE), which, while small, contains a relatively newer state-of-the-art radar sensor that might give some equivalence to Russia’s versions. Perhaps more importantly, the purchase included a year-long subscription to radar data of regions of concern from ICEYE’s nearly 20 other satellites. However, the upshot of these stories is that with very little investment, the Ukrainian government has access to more space assets than the Russian military, much of it likely using more modern technology.

Then there’s how Ukraine is using these off-the-shelf commercial technologies–it’s combining them. GIS Arta, an Android application, is the most interesting example of how Ukraine uses space to its advantage. The app is commonly referred to as “Uber for artillery.” The Ukrainian military has been using GIS Arta since 2014. At the start of the Russian invasion, it relied on a Viasat satellite to work. But Russian hackers jammed Ukraine’s access to Viasat’s satellite.

Enter Starlink, which Russians also attempted to jam but failed. Because of Starlink, Ukrainian commanders have access to a real-time battlefield map. Moreover, those maps can come from drones or imagery satellites. This allows field commanders to identify Russian targets that require servicing quickly. Ultimately, GIS Arta, using updated imagery and satellite communications, allows a Ukrainian artillery, mortar, or drone unit to eliminate targets within 45 seconds of target identification (instead of as long as 20 minutes).

It may be that even the U.S. military can’t respond as quickly. If so, then that is a concern, as it has also spent billions on unique, hardened space and ground equipment.

Whether the U.S. or Russian military, both had the opportunity to develop a very similar system to GIS Arta. In the world of large military budgets, it's doubtful that the software costs much more than a few guided munitions. But, of course, what makes that software effective is a multi-billion dollar LEO broadband constellation with easily relocatable satellite terminals. The result shouldn’t be surprising: terrestrial internet infrastructure similarly facilitated all sorts of software applications for decades. It continues to do so.

The space power imbalance between Ukraine and Russia and the dissonance displayed in the real-world results require a hard look and harder questions about what “space power” is. Based on Russia’s example, operating many expensive and exquisite large satellites doesn’t indicate the true power of a nation’s space assets (as its military seems impotent in its use). So there’s something else going on, possibly to do with training and doctrine. Or corruption.

However, mindlessly repeating the mantra “go commercial” does not answer questions about space power, even if commercial space assets and data contribute significantly to Ukraine’s battlefield successes. None of those would have been helpful if Ukrainian leaders had squirreled the data into a vault. Instead, their clever use of Starlink (and other space communications systems) demonstrates what is possible when used with software applications and other satellite-supplied data.

But is that space power? Is it the systems a military puts into orbit? Unfortunately, this Space Force document doesn’t honestly answer that question:

“Military spacepower is the ability to accomplish strategic and military objectives through the control and exploitation of the space domain.”

That’s a squishy definition straight from the military buzzword generator with questionable criteria. Ukraine didn’t need to control the space domain to exploit its characteristics effectively.

There’s definitely something to be learned from that.

Comments ()