Hurricane Helene, Space, and All the Data

Before starting, I am not a meteorologist. I don’t even follow the weather as a hobby. However, the shift from living in Colorado Springs to St. Petersburg, Florida, has made me aware of the weather, primarily because of hurricanes. This brings me to my next point–I am a recent Florida resident—less than five years here—so the prospect of hurricanes coming even close still introduces higher states of anxiety in me as they become known. Some of the more extended residents appear to have a…more relaxed(?)..attitude toward hurricanes.

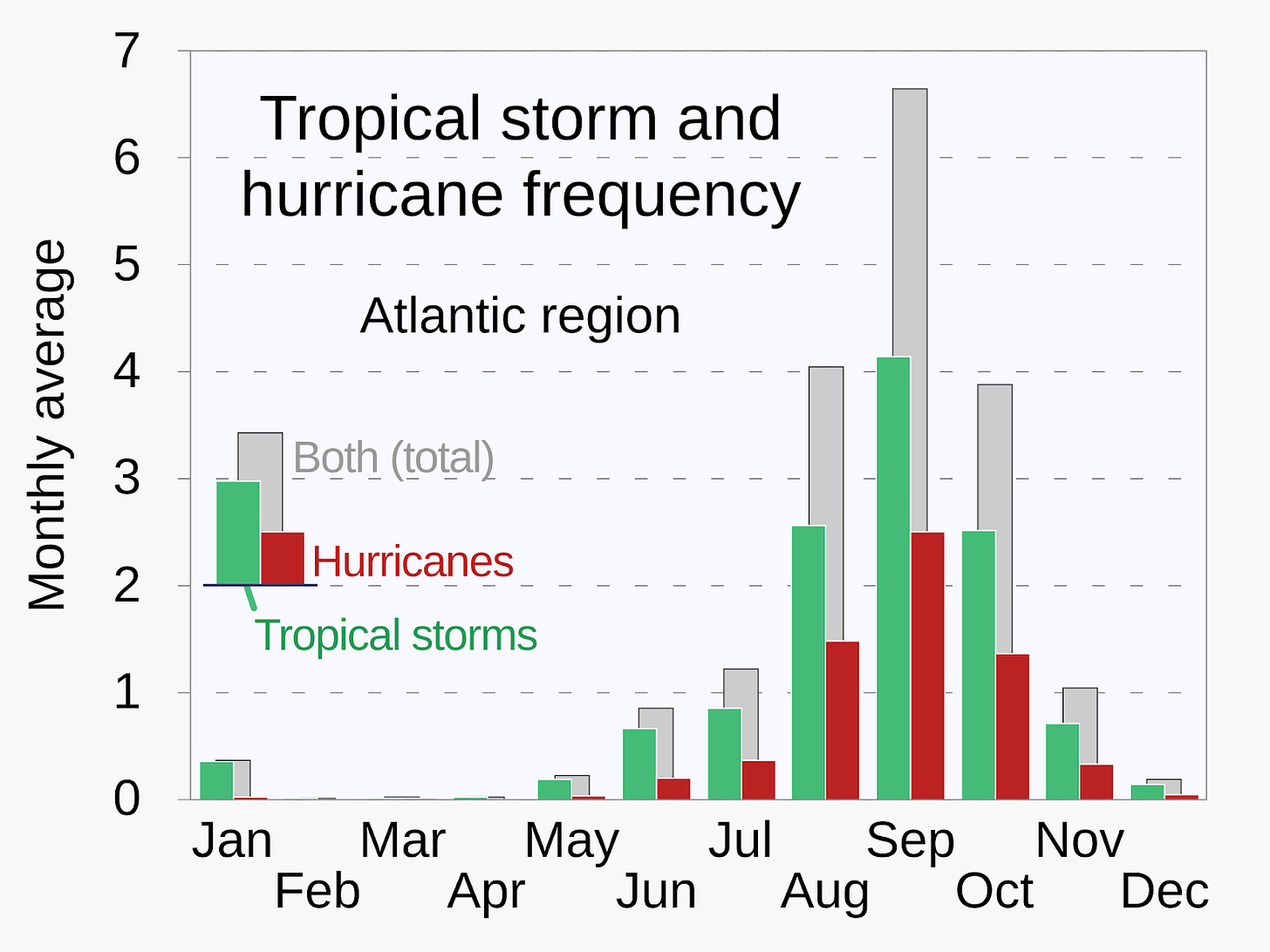

Since living here, though, I’ve learned a few things. I knew that hurricanes were seasonal, but I didn’t realize hurricane season’s length. I certainly didn’t understand that Florida’s hurricane season (the Atlantic’s, really) was six months long, from June 1 through November 30. And that the height of the season is in the first few weeks of September (as seen in the Wikipedia graph below).

The local forecasters actually do a really good job of repeating this information as the season approaches and throughout. They do it every single year. No one who pays even a little attention who lives in St. Petersburg can claim ignorance of hurricane season. Even in my five years, I’ve noticed that hurricanes tend to come close to St. Petersburg in August (Idalia and Debby) and September (Ian and Helene). And that’s me, a casual observer. The local forecasters and federal weather watchers have better data to rely on.

Helene’s Eye Out West (and its Impacts)

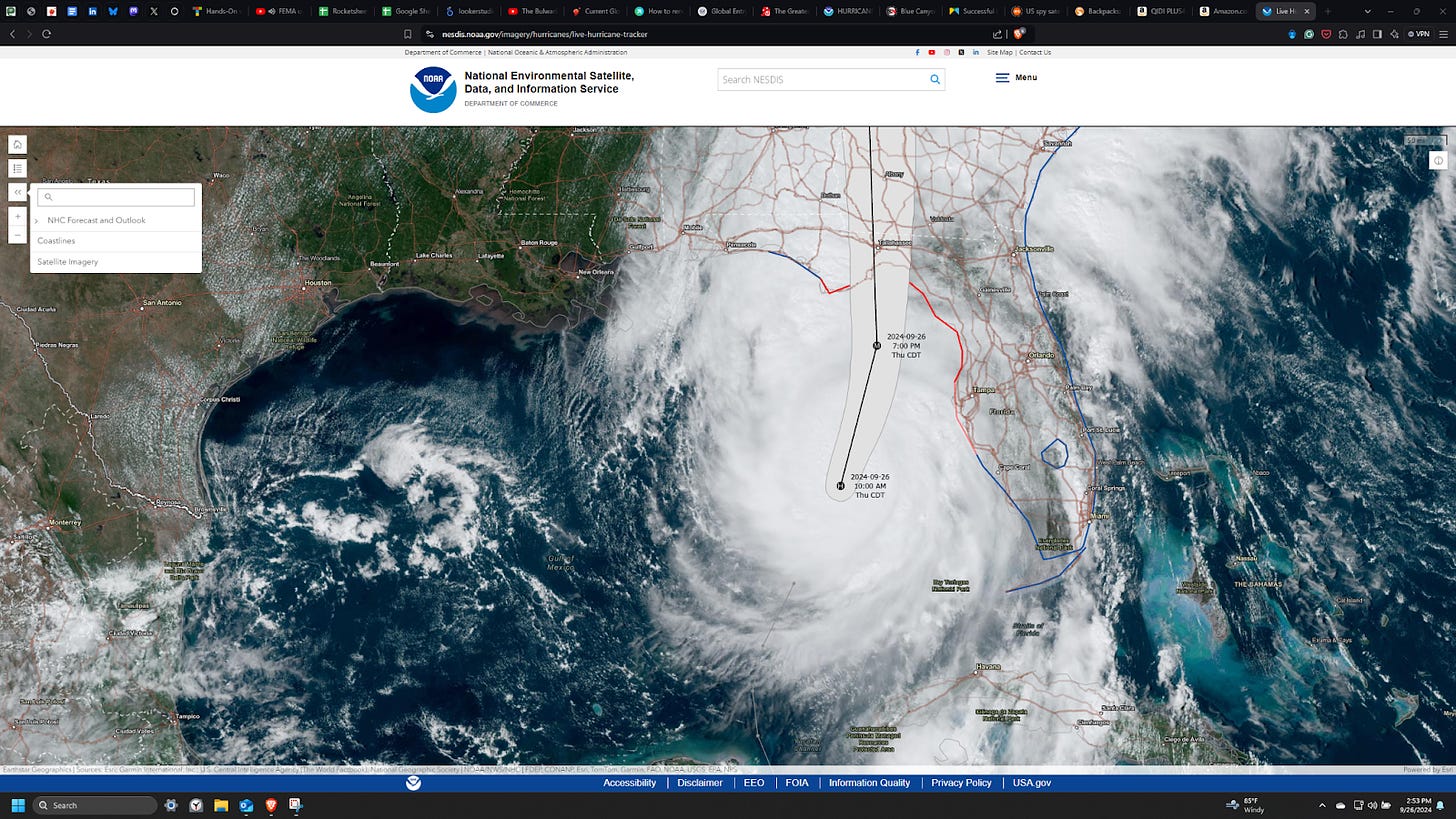

When I started writing this piece, Hurricane Helene was about parallel and ~100 miles west of St. Petersburg. All bridges to our peninsula were closed due to flooding (not as dire as it sounds). Thankfully, the hurricane passed St. Petersburg and Tampa. Unfortunately, it hit Florida’s panhandle (the Big Bend region) and wrought havoc on Georgia and states further north.

Hurricane Helene is the fourth hurricane I’ve had to worry about during the four years we’ve settled in St. Petersburg. So far, and I am incredibly thankful for this, none have directly pushed through the peninsula on which the city sits. That’s not to say St. Petersburg and Tampa don’t suffer any consequences from these storms (Hurricane Helene caused a lot of flooding and damage), but not being directly in a hurricane’s path is, using a technical term, groovy.

Still, when local forecasters begin using words such as “unprecedented” and “record-breaking” to describe a weather event’s consequences, it's worthwhile to pay attention to what’s happening.

They mentioned those words frequently when talking about Helene.

The following bullets provide a summary of how not being in the path of Hurricane Helene still impacted St. Petersburg:

- Storm surge:

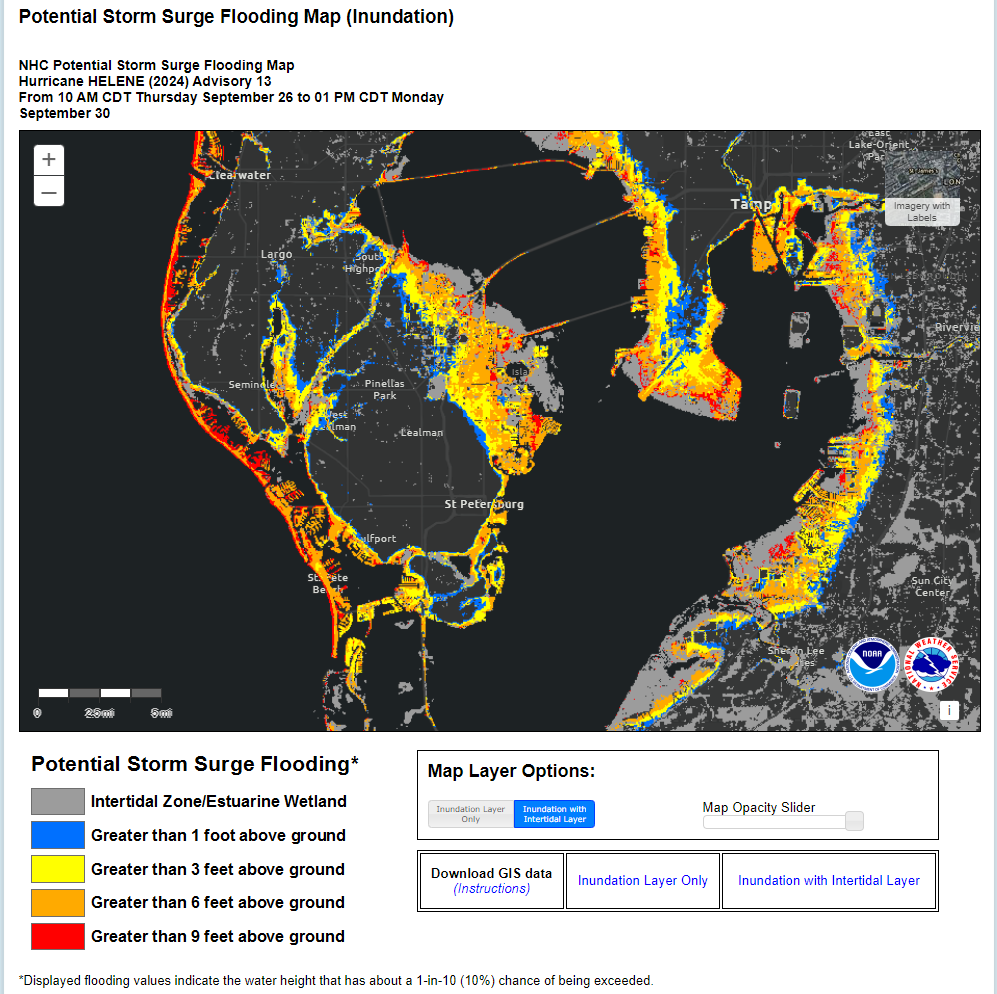

- projected at 5-8 ft (~1.5-2.5 meters) above ground level

- actual: 6.31 ft (1.9 m)

- prior record: 3.97 ft (1.2 m) in 1985

- Wind speeds:

- projected to reach at least 74 mph (119 km/h)

- actual: 82 mph (132 km/h) gusts

By the way, my family and I are fine. We experienced high winds, sideways rain, and a 24-hour power outage. The only things that were spoiled were our hygiene and some food. That’s about it. We were fortunate.

The peninsula’s barrier islands and low-lying areas are a mess (an understatement), and those living there face life-changing decisions. Authorities didn’t allow residents to return to the islands until a couple of days after the storm, and the public wasn’t allowed access until six days later. But I believe most people in the Tampa Bay area are thankful not to have been in the hurricane’s path.

On the other hand, Florida’s Big Bend took the brunt of Hurricane Helene’s 140 mph (225 km/h) winds, a Category 4 storm. The storm surge was predicted to be 15-20 ft (4.6-6.1 m) above ground level. Preliminarily, it looks to have caused a 15+ ft storm surge. The storm’s wind field was 390 miles wide (627.6 km), but its impacts were much more expansive, covering Florida entirely for a few hours. And, as of October 1, 2024, Helene still impacts communities further north, in Tennessee and the Carolinas.

It sounds terrible, but it could have been worse. Millions live in Tampa’s metro area, and hundreds of thousands live on Florida’s Gulf Coast. The storm’s overall U.S. death toll so far is low (compared to the populations impacted) but climbing. The deaths from the storm are tragic, and those people will be missed by loved ones and friends. Simultaneously, it’s miraculous that millions lived through the storm despite the upcoming hardships facing many of those survivors.

I suggest that the U.S. government’s investment in weather expertise and technology, especially technology for observing the Earth from space, were critical parts of toolsets that helped keep many people alive as the hurricane passed through Florida. At least, that's my experience during the years we’ve lived here. Thanks to the feds and the forecasters, there was plenty of warning–at least for Florida and Georgia. I’m not sure anyone expected Helene to be so deadly further north (in the mountains??!!).

This Data Needs to be Free

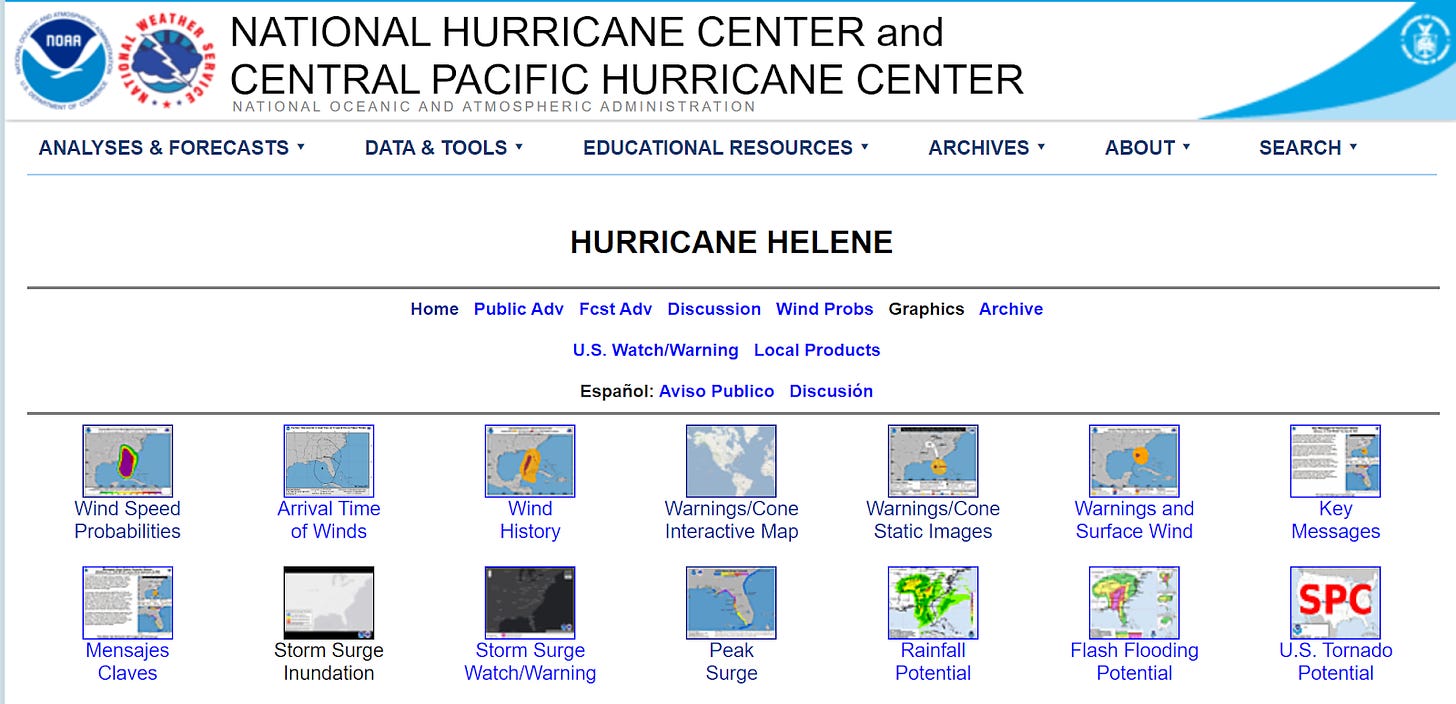

With every one of these events, I’ve learned to use tools to monitor a storm’s progress and determine whether it’s time for the family to throw everything in our cars and scram. Some of those tools rely heavily on space technology. All of that technology merges with other tools to provide valuable and actionable information on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Hurricane Center dashboard. These tools are free to the public and easy to find. It’s available on smartphones, too.

When you get to the NHC’s dashboard, you will immediately notice that none of the information is written in Sharpie. Unfortunately, it does look like a site created at the height of Yahoo! GeoCities.

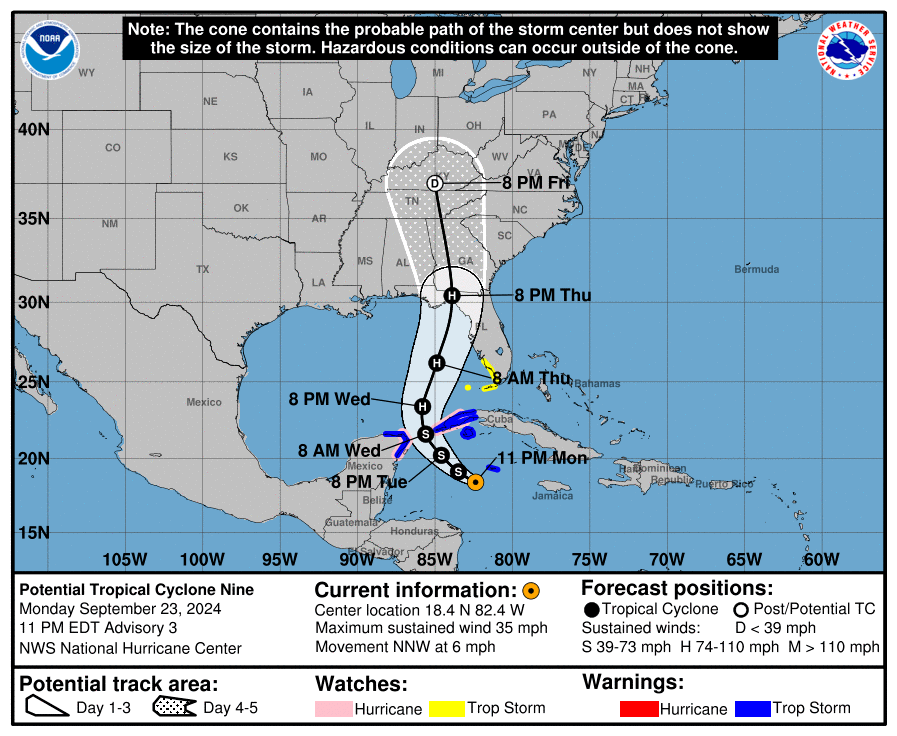

All the critical information is there to be clicked on and absorbed. The Warnings/Cone and Storm Surge Inundation graphics are most important to my decision-making. Each graphic is updated every few hours (I wish there were a visual cue to show which graphic was the latest to be updated).

The Storm Surge Inundation data updates on Thursday, as Helene passed by St. Petersburg, didn’t differ much from Tuesday’s update. Both provided a good idea of where not to be when the water started surging. The same could be said for the uncertainty cone models in this case (sometimes these storms “zig” instead of “zag”), providing more confidence in the direction Helene was taking each day. Note that on Monday, the cone covered St. Petersburg. By Wednesday, it had moved west.

All the Data (including from Satellites!)

The data NOAA uses to provide the comprehensive information in these graphics should be a model for any space business and its plans. Strangely, it’s valuable and helpful because it uses more than data from space technology alone to give U.S. citizens a heads-up. However, like missile warning satellites do for defense, meteorological satellites are key tripwires for when an area needs to be monitored more closely and frequently. NOAA owns eight satellites and operates seven others.

Geosynchronous Operational Environment Satellite-East (GOES-East, aka GOES-16) probably provided the overall big-picture tracking of Hurricane Helene. It can image the Earth’s disc every five minutes, and smaller images can be taken every 30 seconds. A GOES satellite provides all sorts of data, from optical to infrared. The Joint Polar Satellite System satellites (JPSS), in a sun-synchronous low Earth orbit, also provided updated data, probably cued into monitoring the storm once it was initially detected.

Then, there are the Time-Resolved Observations of Precipitation structure and storm Intensity with a Constellation of Smallsats (TROPICS) 3U cubesats. The satellites are designed to observe tropical cyclones. They overflew Helene every hour, providing additional frequent updates about the storm. In short, NOAA and the U.S. government have many space assets to not just warn but also provide data to help characterize and then accurately forecast a hurricane.

In the case of Helene, the satellites provided the nudge to action about four days before it made landfall on Monday, September 23, 2024. Those days were critical.

On Tuesday, state governments issued emergency management orders, which, in turn, activated emergency response assets so they could deploy throughout the state. The same day, the U.S. president started issuing emergency declarations, authorizing the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to coordinate disaster efforts and make emergency effort funding available. Local authorities got ready as certain zones were notified they were to be evacuated. All these authorities tried to communicate to locals the potential severity of the storm.

In other words, no authorities were caught off-guard by Hurricane Helene despite its origin over 700-800 miles away on the first warning and its rapid traversal of the Gulf of Mexico. They used other assets–buoys, aircraft, etc.- to get more data to determine the path the hurricane would likely take. Again, satellite data is only partially helpful, but it helps to buy more time for other necessary actions. And the authorities did what they could to communicate with communities about the storm’s potential impacts and essential actions, such as leaving.

In my experience, I maintained a solid situational awareness of what was happening by using these free tools and watching the updates. But, like I said, I usually don’t watch the weather. My awareness relies on tripwires, which local news channels supply, which then causes me to pay close attention. Some channels use more than NOAA data to provide more certainty in their hurricane models. I also watch local forecasters because they have hurricane monitoring/interpretation expertise. I do not, so their information augments what I see on the NHC dashboard.

Ultimately, it’s incredible that the tripwires and such a comprehensive suite of tools are free to the public. Not only is it available, but it’s in demand: I believe many of us used the data in some way to help guide us through Helene. They’ve also improved over time, which is amazing when thinking of the variables involved in a hurricane’s genesis.

Compare the government’s service and results to the promises from commercial remote sensing companies. Those companies are still struggling to identify any kind of profitable demand for their business plans. To be clear, it’s appropriate for the U.S. government to provide this weather data for free. People’s lives depend on it. Any talk of stopping or planning to stop that provision of life-saving data by breaking up NOAA is simplistic, myopic, and irresponsible[1].

In the meantime, NOAA is gathering this information to help the U.S. military and for agricultural reasons so that some taxpayer money would be spent on these space systems anyway (NOAA usually operates military weather satellites). It’s great that it can also help keep the public safe.

For those wanting to donate to help Hurricane Helene victims, the Red Cross has a few options for you: https://www.redcross.org/donate/dr/hurricane-helene.html/.

If you’d like to take a more active role, then try the National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster site: https://www.nvoad.org/hurricane-helene-response/.

*If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), I appreciate any donations (I like taking my family out every now and then). For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU from me and my family!!

*Either or neither, please feel free to share this post!

**

And yes, several someones are pushing for the idea of breaking up NOAA. See page 674 of Project 2025 (https://static.project2025.org/2025_MandateForLeadership_FULL.pdf#page=707) –it literally starts with the words “Break Up NOAA” and gets worse at the NWS section. There’s a place for commercial businesses in weather, but emergency weather operations using sources of data garnered from various technologies that need to be free to the public ain’t it, chief. More about this in a later newsletter. ↩︎

Comments ()