Focus On: ULA's Challenges, Part 3

The earlier part of this analysis highlighted the United Launch Alliance’s (ULA) challenge in gaining commercial customers. Unfortunately, at least until the company fields its Vulcan rocket, there’s probably not much more cost-cutting that can happen without ruining the company.

Can it wait that long?

I Reject Your Reality & Substitute My Own

ULA is steadfastly adhering to its strategic plan, despite changes in the launch sector that will adversely impact ULA if it continues with these current assumptions. While “staying on target” is admirable, Tory Bruno, being the very smart man he is, is surely observing these changes. He may believe in his heart that perhaps the strategy underlying his company’s plan may not provide as much chance for success as initially believed.

The plan, likely implemented after Bruno became ULA’s CEO, appears to be based on a few assumptions:

- The U.S. government will continue supporting ULA

- There’s room in the U.S. market for two competitors

- The upcoming Vulcan rocket will make ULA more competitive

The previous analyses addressed ULA’s challenges identified in the first bullet. Yes, the U.S. government will continue supporting ULA, largely because of two reasons--familiarity and reliability. However, the company won’t continue receiving the extraordinary premiums it commanded when it had no competition.

As concerning for ULA, SpaceX is also becoming more familiar with the U.S. government while providing a reliable launch service for significantly less than ULA’s prices. SpaceX’s very aggressive pricing for its services and its ability to launch quickly increased pressure to lower launch prices faster than ULA expected.

While there appears to be room for at least two U.S. launch service providers to the government, the government is awarding some contracts to SpaceX, eating into ULA’s launch opportunities. Non-ISS-related U.S. government missions averaged around ten launches from 2011-2020 (with little variation). That average indicates no upcoming trend of dramatic increases in government missions, even as SpaceX provided more launch opportunities.

ULA, then, must get past relying on government contracts and aggressively gain other customers for its business.

Launch Model Mania

ULA could do more than lower prices, however, to attract customers. One way is to increase the types of launch services it provides. ULA could provide another outlet for smallsat launches as part of a rideshare program (a service SpaceX offers). ULA considered offering these alternative services using its current rockets. With the latest SBIRS GEO-5 launch, we saw that ULA could deploy smallsats as well as a primary payload. The white paper and the latest launch indicate ULA’s capability to conduct rideshare operations. So why doesn’t it do it more often with more small satellites? Especially since there are customers out there who would pay?

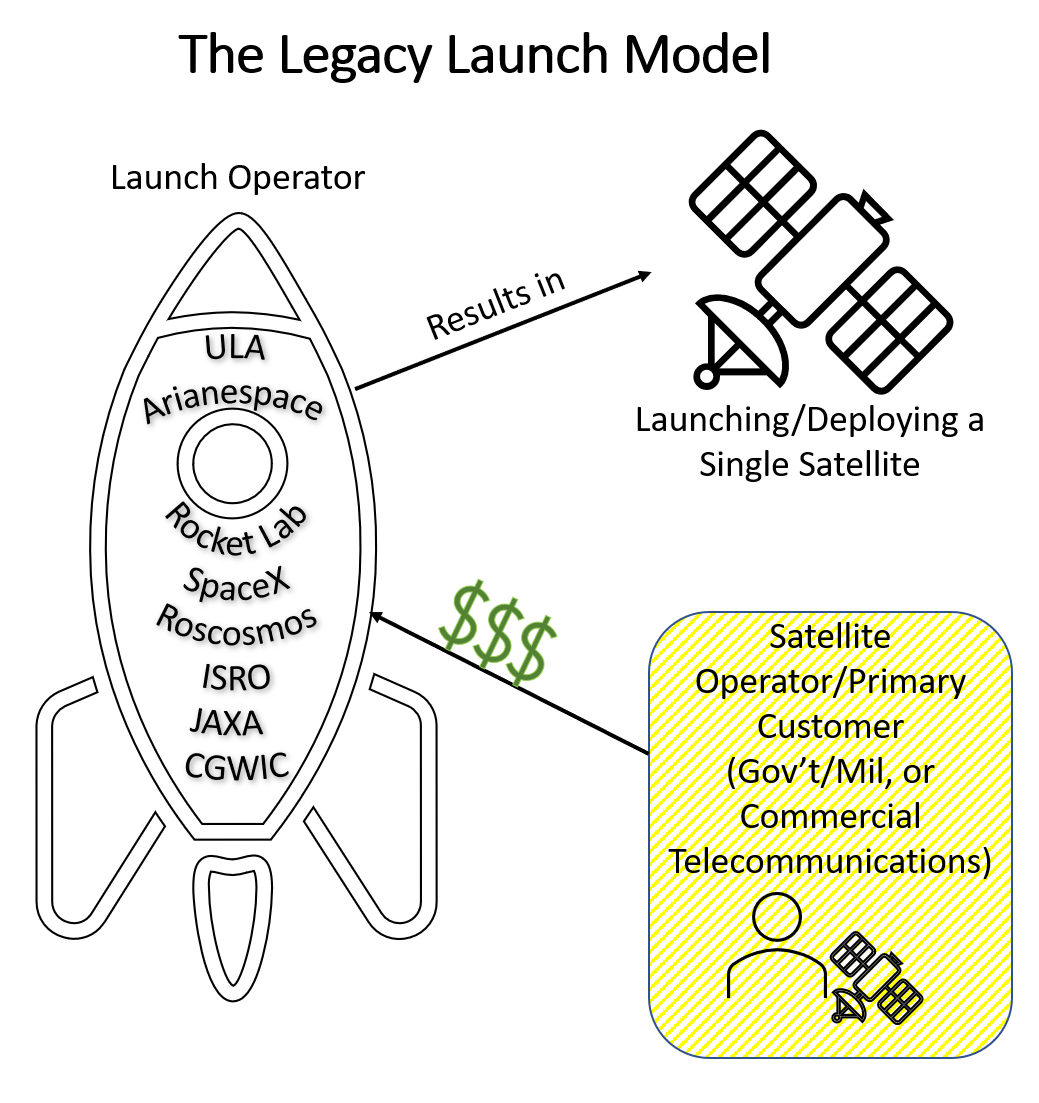

While ULA occasionally conducts rideshare launches, it is more often associated with launching a single satellite for a single customer. Since this is how rockets have been used through their brief history, I’m calling this the legacy launch model (below):

Note ULA is not the only launch service provider that does this type of launch (also, in the model, CGWIC serves as a proxy for all of China’s launch companies). Every single operational launch service provider can launch and deploy a satellite this way. This launch type may be desirable to a customer who doesn’t want to “share” a launch. As established, ULA was making a lot of money from launching a customer’s satellites one at a time.

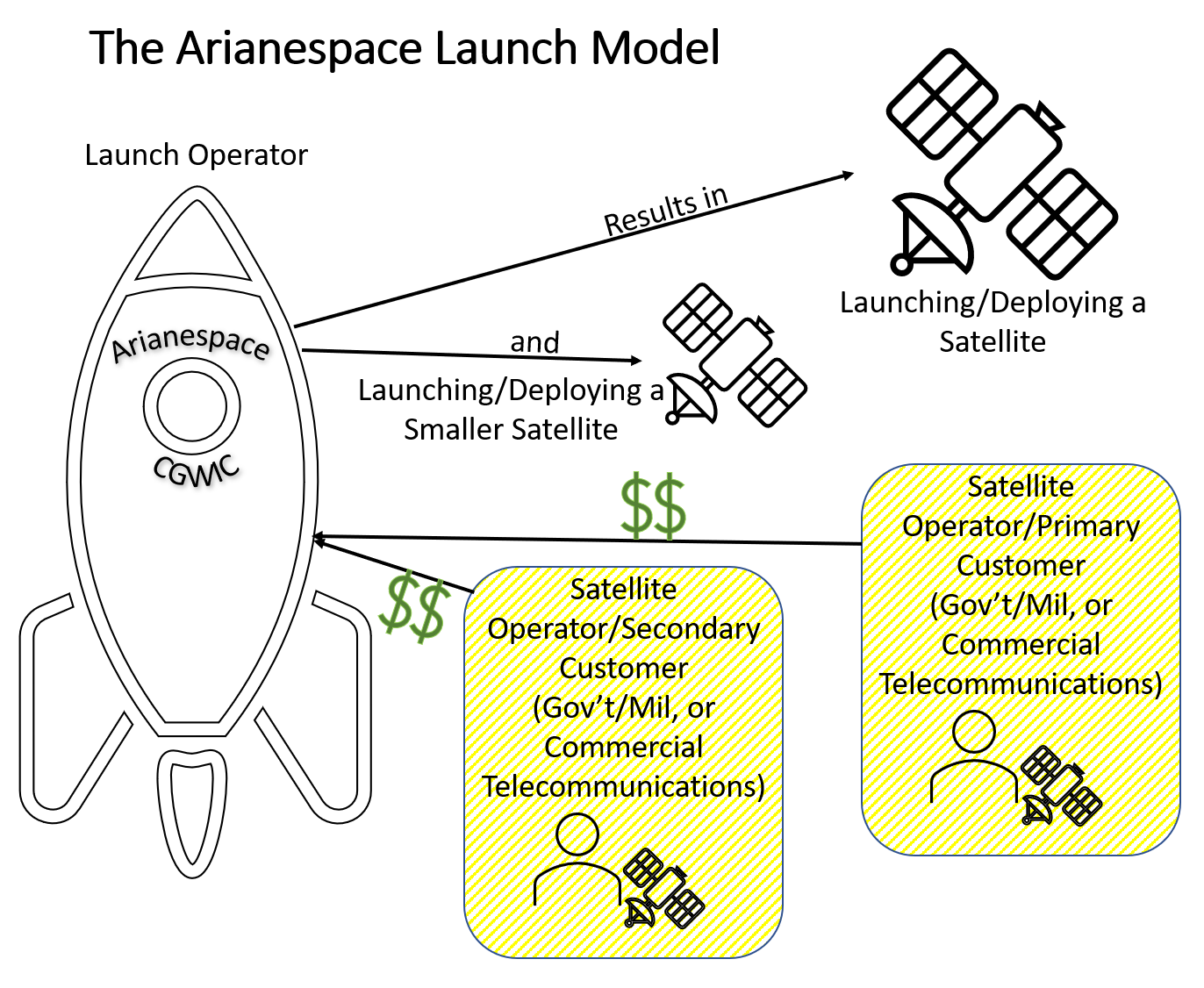

There are other launch models, ones that deploy more than a single satellite. They have become so common that concerns about potential dual-use implications have faded into history. Starting with a particular method that Arianespace usually employs for its Ariane 5: deploying two satellites.

Arianespace uses that method to allow customers to “split” the cost of a launch. That split is usually why Arianespace’s management argues that an Ariane 5 costs customers much less (although the aggregate launch price is still relatively high). Of course, this only works if customers don’t have a less expensive option to turn to, and that political unity, not company business, is an important consideration. But Arianespace’s way of deploying multiple satellites from Ariane 5 is just the start.

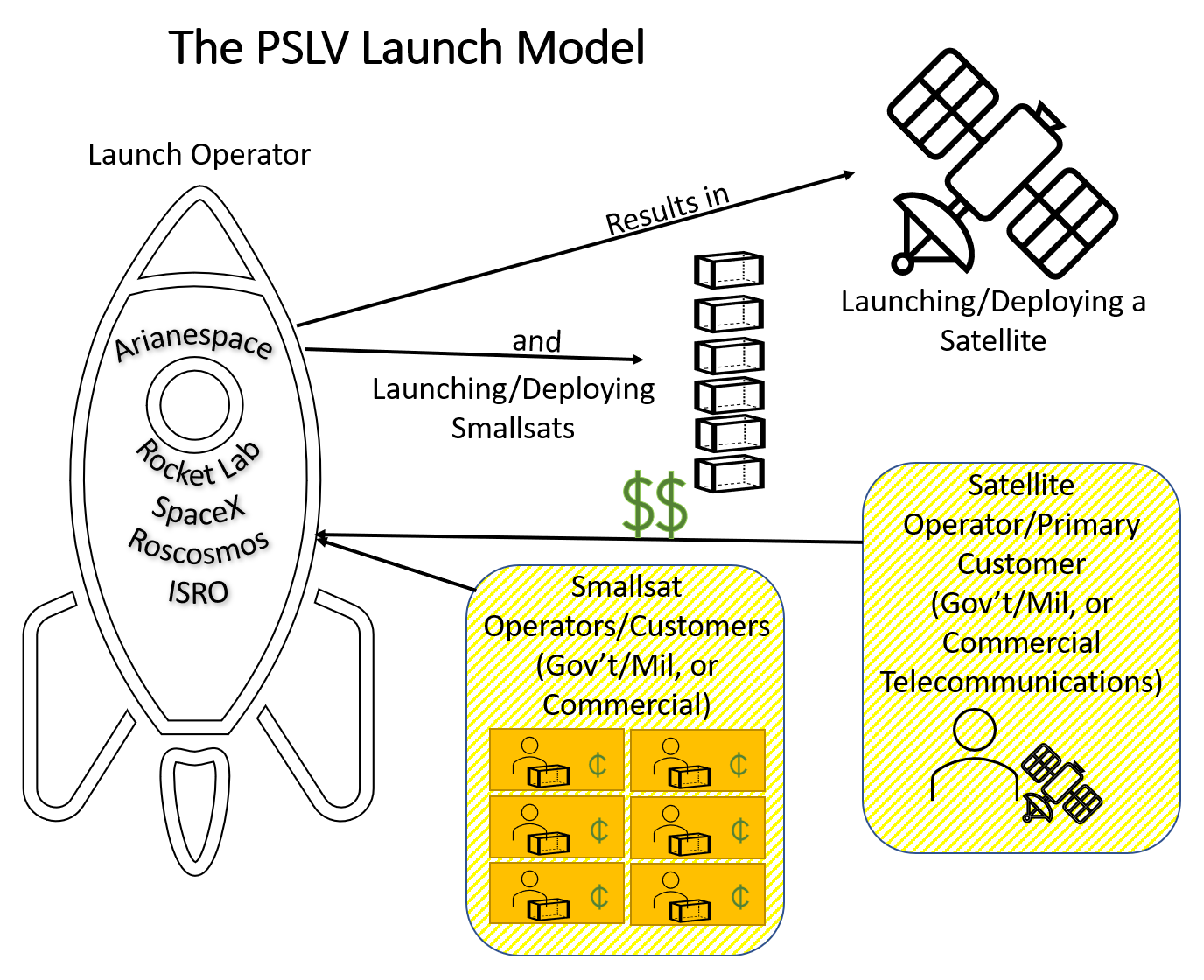

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) often launches its Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) with a primary satellite and many small ones. These satellites are much smaller, typically cubesat-sized, than two satellites deployed on an Ariane 5. India uses the PSLV to significant effect, with many foreign smallsat operators attracted to launching on one. The PSLV was the first rocket to launch over 100 satellites in one go.

One challenge for launch service providers using this type of satellite deployment is that each customer pays much less for deploying their satellites than the primary customer. But, if there’s an option to deploy many smallsats belonging to many customers, then maybe there’s enough to make up the difference. The ISRO may be making more with its many rideshare customers on its PSLV than it would if it deployed only two satellites.

ULA does this type of launch now and then in smaller batches. But it provides smallsat operators a satellite berth for free. That situation is excellent for a satellite operator but a terrible precedent for ULA, throwing away an opportunity to get money back. Once a company gives something away for free, people expect it to remain free. Will ULA continue offering free cubesat rideshare opportunities when it’s launching for a lower price? If ULA wants to make money, that doesn’t seem like a great idea.

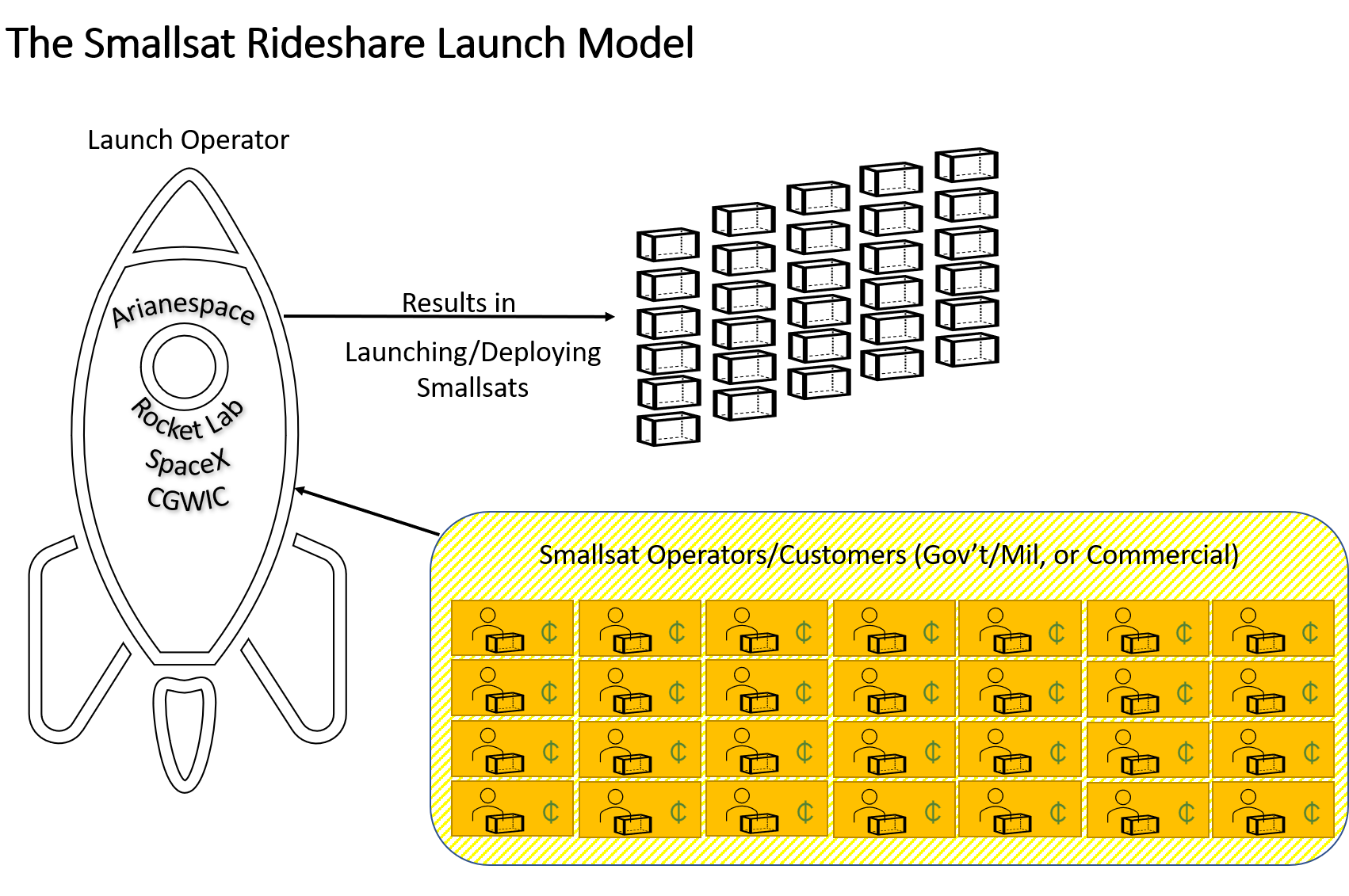

From the PSLV launch model comes a logical step--full rideshare (no primary payload). The operators taking advantage of full rideshare launches typically operate small satellites. Depending on the launch vehicle, the number of smallsats can go from tens to over a hundred. That’s taking rideshare to the 11!

The drawback of such a model is that the launch provider must have a single customer with many smallsats for its rockets or many customers with enough satellites to pay for the rocket launch. All the models show the drawback of relying on smallsats for a launch business only: the cents need to add up to dollars for every launch. Large satellite launchers have an inherent advantage in this regard. None of the smallsat-dedicated launch providers have a large dollar launch capability, whereas companies like SpaceX and ULA can adjust “down,” launching smallsats as required.

Getting Out of the Comfort Zone

While there may be other ways to deploy satellites from rockets, the point is that each way is a business opportunity for a launch service provider. ULA seems to have ignored those opportunities, hoping instead that its strategic plan survives contact with reality.

Rather than rely on a single primary customer (and occasionally offering free rideshares), ULA should try to expand on the kind of launches it conducts. Based on ULA’s white paper, the company can configure its rockets to deploy satellites in nearly all the ways observed above. It seems to be something the company should be seriously considering--especially when SpaceX’s Rideshare program seems to be successful.

So long as the company keeps per kilogram pricing below Rocket Lab’s $25,000 mark, ULA would attract smallsat customers. And the company could indeed be competitive against Rocket Lab’s Electron. The price awarded to ULA for launching the 4,500 kg SBIRS GEO-5 to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO) was ~$150 million. That comes to $33,000 for each kilogram of mass--close to what smallsat customers were paying Rocket Lab initially for an Electron launch (and maybe cheaper than Arianespace’s Vega). Also, the Atlas V 421 used for the launch could have carried an additional 2,390 kg to GTO. That’s plenty of mass availability for smallsat customers. It’s more than any smallsat-dedicated launch service provider offers.

More importantly, these are paying customers, and Rocket Lab’s success in attracting plenty of customers with that price or higher should be heartening for ULA. It may turn out that for ULA, every little satellite will count. It does for SpaceX and Rocket Lab. Offering smallsat rideshare options also benefits ULA in that it creates relationships with customers worldwide who may have larger satellites to deploy in the future.

Expanded services are just one aspect ULA could consider to increase its customer base. Transparent pricing would undoubtedly help draw customers in, too (Rocket-builder is not transparent). ULA can implement these changes quickly, without substantial reworking of existing launch vehicles. It can do it without changing Vulcan. But will it? ULA’s currently acting like an established company (no surprise). If ULA’s assumptions that created its strategic plan are no longer valid, then it needs revisiting, revising, and maybe even ripping up.

Vulcan is the other sore spot for ULA. If the company was facing any other launch company but SpaceX, the Vulcan might have served a more competitive role. But ULA is building the Vulcan at government-style pacing, not a SpaceX pacing. Worse, its engine supplier, Blue Origin, appears as if it can’t even keep up with government-style pacing, as the engine is not ready yet. Because of this, ULA is forced to use older rockets for contracts that originally were to use Vulcan.

There is certainly a pride point in providing extremely reliable launch services to the U.S. government. Will pride prevent necessary change? Even so, these changes might only serve to allow ULA merely to exist to get to another business phase. Its primary competitor, SpaceX, is constantly evaluating and adjusting its strategy. It’s a big adjustment for ULA as the company has never faced competition, much less competition from quick-moving SpaceX.

Bruno might understand that ULA is reaching the end of a phase (and hoping for a series of phases). That end can provide ULA an opportunity to behave differently, maybe even become entrepreneurial in its behavior, and gain more customers for its services. But pinning the company’s fate and business changes on Vulcan, especially with Blue Origin underperforming in the rocket engine delivery department, may prove a fatal decision, especially if ULA attempts to conduct business as usual with Vulcan.

Comments ()