Focus On: ULA’s Challenges, Part 1

NASA and the Department of Defense have implemented initiatives that are supposed to shore up the current U.S. launch services and maintain a “launch market.” But of the two leading large rocket launch companies in the U.S., SpaceX and the United Launch Alliance (ULA), the latter has lately been only launching government satellites. SpaceX, on the other hand, has launched not only government satellites but commercial satellites as well.

ULA’s government focus poses a problem for ULA.

It is one of many problems ULA is facing in the current launch services sector. Its dependence on government missions has led to a decreasing number and share of the world’s launches (even as the company has gained significant high-value contracts). Its high pricing drove away commercial customers wishing to remain solvent after a satellite launch. However, ULA’s government customers are also moving towards paying less for launches, as discussed below.

While inexpensive launches are suitable for the customer, can ULA adjust its business and adapt? It has a great starting position, after all. ULA has, more than any startup, a significant capability that it brings to the launch sector. It already has the infrastructure and supplier relationships to build new rockets. It has a loyal customer base. Its launch record is a gold standard for reliability. Its rockets are very capable. It has Tory Bruno, an actual rocket engineer who is steady, rational, and one of the company’s biggest fans. ULA could be a robust participant and U.S. representative in a global launch market.

Despite these strengths, ULA’s continued existence isn’t assured.

On to the first part of the analysis!

The Cheapening (of Launch)

When the United Launch Alliance (ULA) launches the United States Space Force’s (USSF) infrared satellite on May 17, it just might be the least expensive ULA launch ever conducted: ~$150 million. ULA is deploying a new addition to the USSF’s Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS), SBIRS GEO-5. The satellite cost taxpayers about $1.4 billion (what’s known in the business as a wagonload of cash). I’ve written up a few analyses here for those interested in more information about the high cost of military infrared systems.

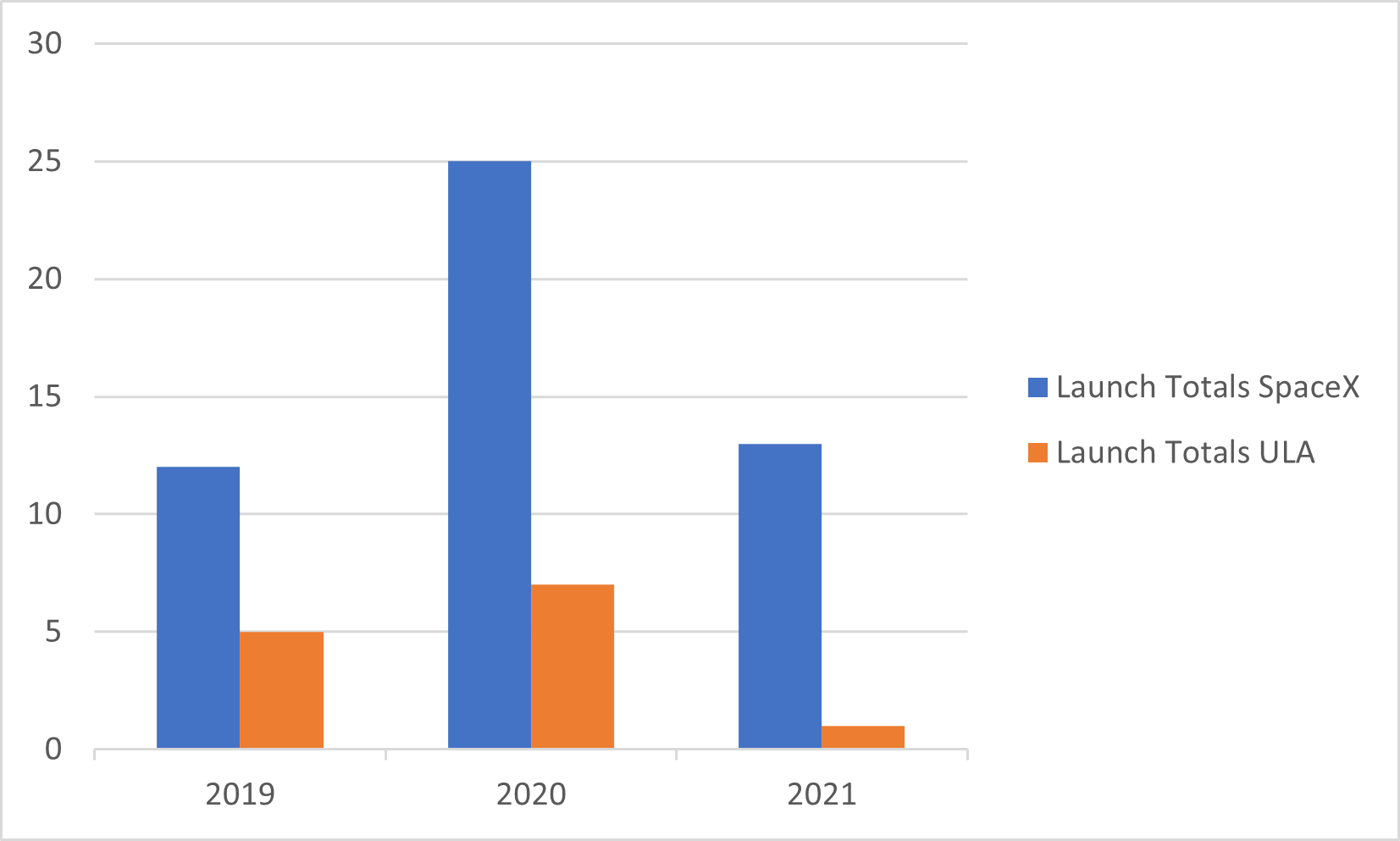

The SBIRS GEO-5 launch will be the thirteenth ULA launch since the beginning of 2019 (the 144th for the company overall). The company used to average about eleven rockets a year until about five years ago. During the past two years, the company is averaging about six launches annually. However, while launches are low, ULA’s customers, NASA and the Department of Defense (DoD), are paying well. In the DoD’s case, it’s paying ULA very, very well.

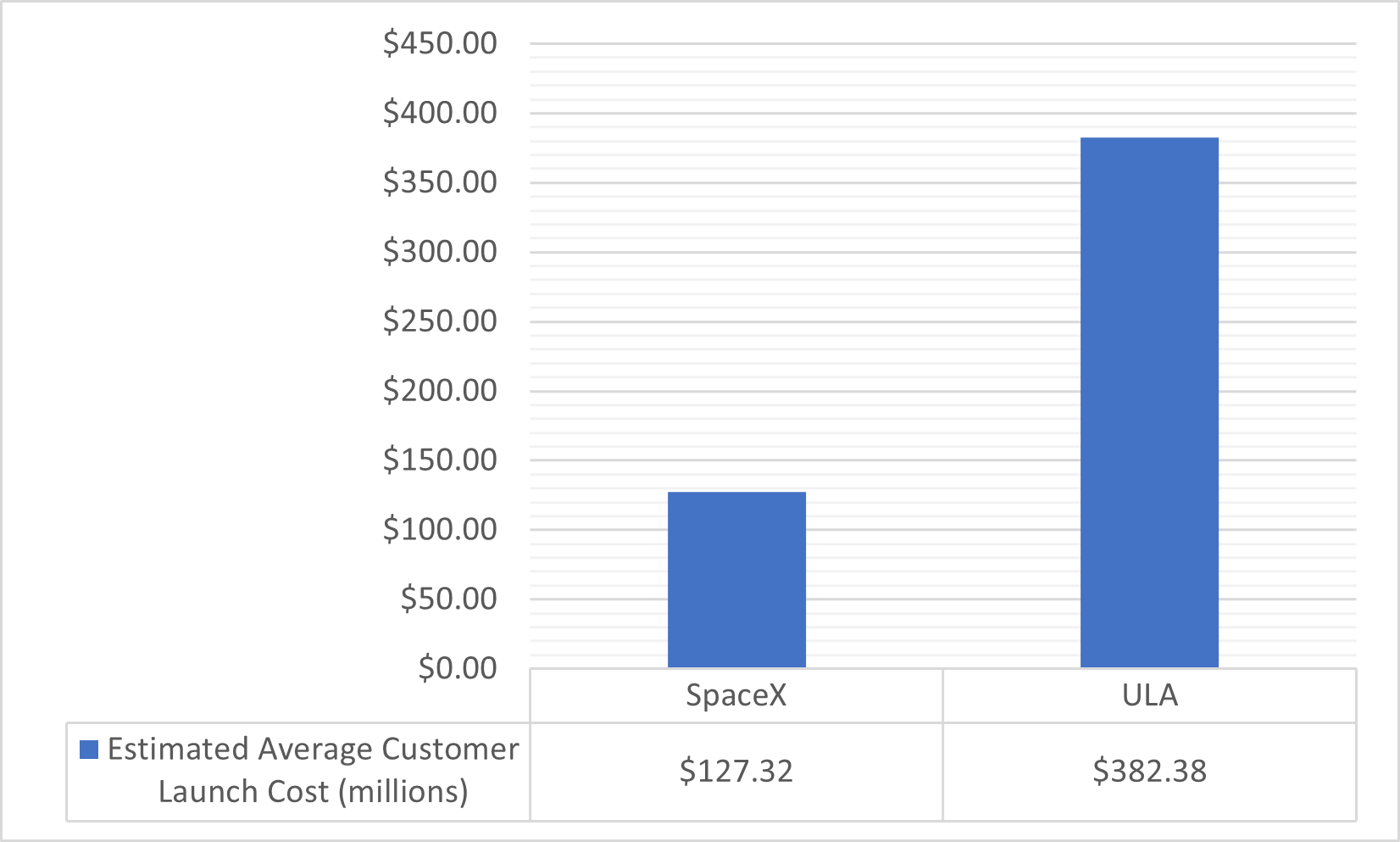

Estimated payments to ULA for its launch services from the two primary customers for all launches since January 2019 (including the upcoming SBIRS launch) come to an estimated $4.59 billion. That averages $383 million per ULA launch (the data comes from documents such as this). It appears ULA was doing okay for the past few years. Perhaps it’s not as profitable as it was before the competition moved in. And if the SBIRS launch price is any indicator, ULA has a challenging road ahead of it--especially if the company wants to keep making nearly $4.6 billion every two years.

However, it may need to change a few things to do so:

- Launch significantly more per year

- Court commercial customers

- Court international customers

- Lower prices

All of the above recommendations are tied together. ULA relied only on government customers for at least the past two years. But six launches annually conducted for a new low price of nearly $150 million comes to “merely” $900 million per year. ULA, however, is also dropping launch prices (~$112 with one of the latest USSF contracts) and will need to launch more than six government satellites to reach even $900 million. That latest drop isn’t competitive when compared to ULA’s aggressive competitor, though.

ULA Needs to Launch (a lot more)

ULA’s rival, SpaceX, is already implementing a way to do this. During the same time, SpaceX launched 50 times--around 25 launches per year. To be clear, 23 of those 50 launches were purely for Starlink satellite deployments. But the remaining 27 paid SpaceX an average of $127 million per launch (for those wondering why the average is so high, it’s the ISS Cargo and Crew launches). Those 27 launches added up to an estimated $3.44 billion for SpaceX. And while that’s not relatively as high as ULA’s total, it’s still respectable.

Even SpaceX’s Elon Musk thinks the potential for profit in the launch business is limited. That profit limit is one reason why Starlink is in orbit today.

So yes, ULA could still profit by conducting more launches, even as the company’s launch prices come down. ULA could, theoretically, produce about 40 rockets a year from its Decatur, Alabama factory. The Vulcan’s tie-in with Blue Origin’s slowly progressing BE-4 engine might be a weak point in that quick production, however. Whether it could launch that quickly is another question.

There are a few reasons to wonder about ULA’s ability to increase its launch rate. The launch rate during the past few years are low. Is it that low because the company laid off about a quarter of its workforce during 2016/2017? Surely the majority of those nearly 900 laid off ULA employees were contributing to ULA’s business in some way. And if they were, will their equivalent be required again if/when ULA does ratchet up its launches?

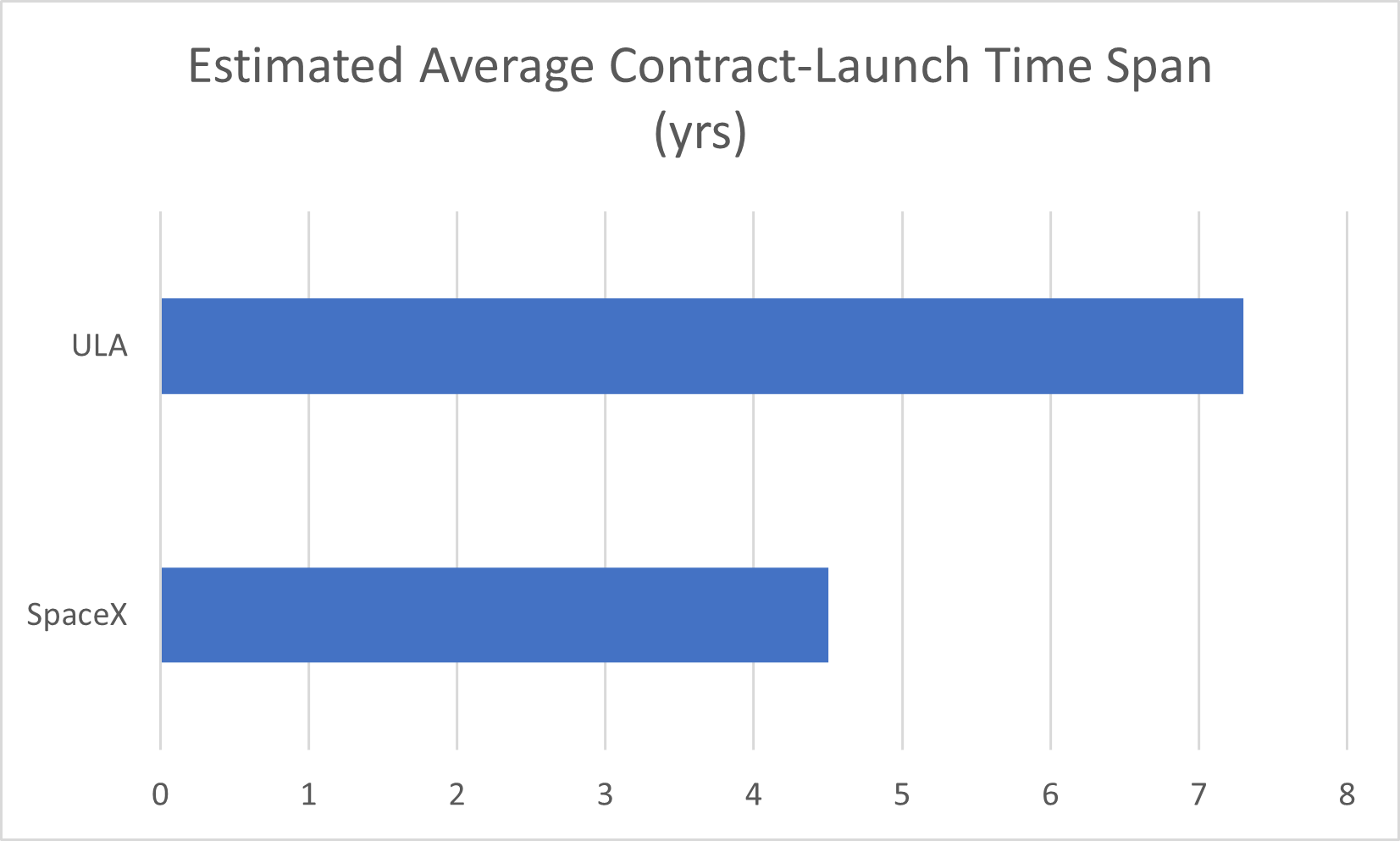

Another reason to ponder whether ULA can launch more rockets in less time has less to do with the company and more to do with its customers. ULA’s customers tend to allow satellites to be produced and launched at a leisurely rate. The company’s government customers take a little over seven years to execute their satellite programs, from a satellite manufacturing contract award to its launch. SpaceX’s customers average about four and a half years for the same activities (it would be much lower if it weren’t for the two GPS satellites at eight years each).

ULA already has adopted much of the practices and behaviors of its government customers. Are the slow satellite program behaviors of ULA’s customers uncritically absorbed into ULA’s launch operations? If it is reflecting its customers’ pacing, how quickly can ULA change that without sacrificing reliability?

**As a quick observation, I’ve always guessed government satellite programs took an average of five years, from contract signing to launch. But the fact that the average is 2.5 years more is eye-opening. And the data I’m using doesn’t include the NRO satellites ULA launches, which are likely as bad or worse than the unclassified satellites. **

ULA only needs to launch about 13 to 15 lower-priced rockets annually to equal SpaceX’s efforts. The company has demonstrated an ability to launch the required annual launch rate at least once in its history. There’s no reason to believe it couldn’t do so again. But there may not be enough launch facilities for ULA’s Vulcan or Atlas 5 rockets to launch that quickly annually.

Is there a market incentive to do so? More about that next week.

Old = New + Again

Back to the USSF. The space service is already a little confused about its priorities. It wants to be the first “digital service,” and while the elders among us may be thinking Tron, it’s nothing so neon. It doesn’t even appear that the digital service will fight for the users, as the following tidbit sums up what these digital “servicepeople” will do:

“The goal is to have its members — dubbed guardians — be digitally fluent and have their space operations revolve around being “an interconnected, innovative, digitally dominant force,” according to its recently published “Vision for a Digital Service” document.”

In other words, the USSF wants people who can be...Millennials?

This digital dominance idea is not new. There’s been lip service about computer networks, cybersecurity, etc., as a part of space (because satellites are computers, and computers are required to talk with satellites) since when I was in the service. I thought those efforts were misguided then. That sort of thought process surfaces in a later Air Force Space Command document from 2012 highlighting “Cyberspace” priorities.

The “Digital Service” goal appears to be another mission the USSF inherited from the USAF. But is it something the USSF should take on? Or is it being pushed by people in the USSF who drank from the cybersecurity/cyberwarrior fountain when they were in the USAF?

And, at the risk of disappointing General Raymond, there’s already a digital service. It’s literally called the U.S. Digital Service. Frankly, the USDS’ mission sounds more well-thought-out than the USSF’s goal for its digital service. More valuable, too.

Comments ()