Focus On: Telesat’s Lightspeed Satellites, Constellation, and Purpose

Oooofff! This analysis is a long one. But I found it interesting to think about. I think you’ll find it interesting, too.

This last Tuesday, Canadian satellite communications company Telesat finally announced the manufacturer for its low Earth orbit (LEO) broadband satellites: Thales Alenia Space (a French company). It’s a brave step for the company to make, considering it only announced its intention to deploy a LEO broadband constellation nearly five years ago. During that time, Telesat has consistently dipped its toe in the LEO broadband pool and backed away...until last Tuesday.

That sarcasm out of the way, let’s take a look at some of the details the company shared about its Telesat LEO (now Telesat Lightspeed) satellites and constellation.

A Limited Field of Manufacturers

Choosing Thales Alenia may be the result of Telesat not having much choice of responsive satellite manufacturers worldwide. It had chosen two manufacturers in 2016, Space Systems Loral (SSL) and Surrey Satellite Technology Limited (SSTL/Airbus), for prototype satellites (one which is on-orbit today). Those companies weren’t chosen for Telesat Lightspeed.

To be clear, Thales Alenia makes excellent satellites. It was the company that manufactured the 81 Iridium NEXT satellites. It managed to do so quickly, allowing Iridium to become operational within two years of the first Iridium NEXT launch. For the time (four years ago!), that was fast.

And that’s the point. Of the existing satellite manufacturers, Thales Alenia is probably the only one that has a chance at building the necessary number of reliable satellites (298), so they can all be deployed by “the second half of 2024.” If Thales Alenia started manufacturing Telesat Lightspeed satellites this month, the company still must manufacture ~7 satellites per month to meet that obligation. No other legacy satellite manufacturing company has demonstrated an ability to build satellites at that rate. They certainly won’t do it inexpensively.

Telesat probably didn’t even consider approaching SpaceX or OneWeb/Airbus to use their satellite busses, even though those companies can manufacture more than enough broadband satellites per month. There would be at least two reasons for this: 1) Telesat probably doesn’t want to fund competitors (even if it’s working an “angle” in the LEO broadband business), 2) neither SpaceX’s nor OneWeb’s satellite busses can hold the mass Telesat is planning for its Lightspeed satellites. Result: Thales Alenia Space is building Telesat Lightspeed satellites.

Lightspeed Details and Comparisons

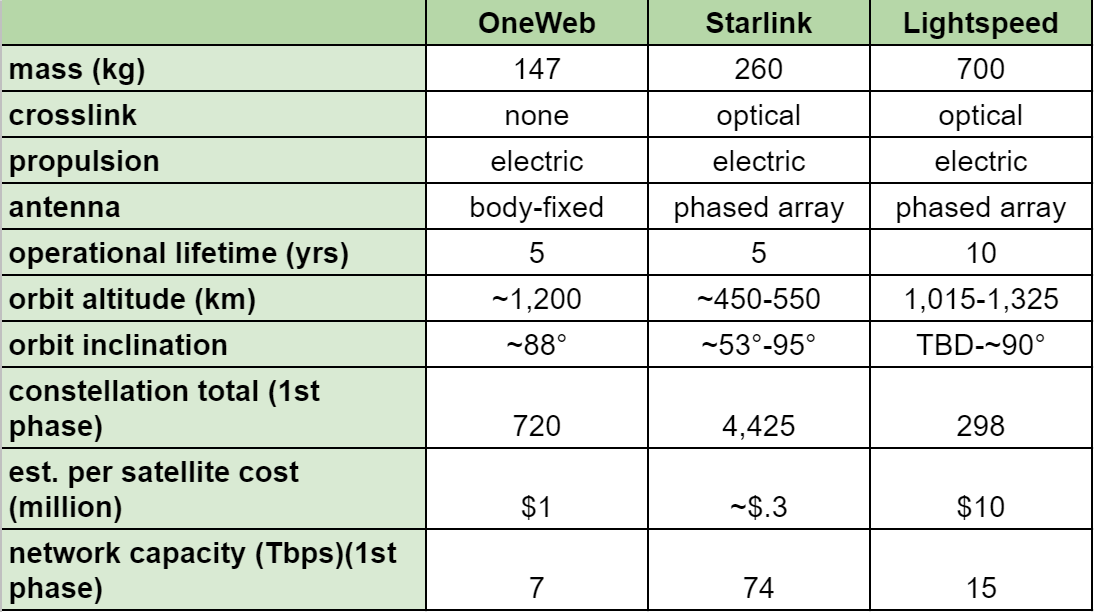

Telesat provided a convenient pdf to highlight Lightspeed’s details. Comparing a few of those details with the other LEO broadband operators gives us the chart below:

Note, the orbital characteristics for OneWeb and Starlink are referencing current on-orbit satellites. Both will be deploying satellites into other orbits.

At a glance, a Lightspeed satellite’s mass is more than a Starlink or OneWeb satellite. It’s equal to a little more than four OneWeb satellites. It will also be higher in orbit than the current batch of Starlink satellites, straddling the altitude at which OneWeb operates its satellites. Its network capacity is about twice that of OneWeb’s, but relatively short compared with Starlink’s (Starlink’s capacity number is based on public statements that each launch of 60 Starlinks=1 Tbps). Lightspeed satellites will have about twice the operational life, ten years. And Lightspeed appears to cost more (based on the $3 billion contract it signed with Thales Alenia).

While I may be repeating a little of the above chart’s data, let’s see what Telesat thinks are the things that make its constellation special. According to Telesat, the following are the “leading-edge technologies and features” of the Lightspeed satellite and constellation (I am paraphrasing the company’s sales pitch):

Satellite phased array antennas.

RF beam hopping

Creates 135,000 beams

Focuses Gbps capacity (the company says this is--wait for it-- “an order of magnitude” more than any system. I wonder who else uses that phrase?)

7.5 Gbps for a single terminal

20 Gbps to a “hotspot”

for “remote communities, large airports or major seaports”

About 1,200 optical links

four per satellite

Data gets passed from satellite to satellite at lightspeed (as expected)

On-satellite data processing using

Digital modems

An operating system

Network capability

Flexible data traffic routing

Data encryption

A satellite constellation with satellites in

Polar orbits

Other orbital inclinations

a “patent-pending architecture” (the company’s words)

While those technologies and features are interesting, they are only that way because this is the first time Telesat has published any specifics about its LEO broadband constellation. It’s easy to see from referencing the chart that, technology-wise, OneWeb is left in the dust. Still, the company has satellites in orbit.

However, Starlink is using similar technologies to Lightspeed on satellites it’s already deployed. Maybe Telesat’s Lightspeed tech is better (the focused speeds are very high), but it’s also clear the company intends these satellites to be unchanged on-orbit for at least a decade. Those Lightspeed satellites won’t begin deployment until the second half of 2023. On the other hand, SpaceX shows no hesitation in upgrading its satellites or architecture--typically within months. It also has satellites in inclined and polar orbits already.

Put it all together, and it’s still not entirely clear WHY Telesat remains interested in operating a LEO broadband constellation.

State of Sector

Before getting to what the company believes is the raison d'être for deploying Lightspeed, it’s worth quickly reviewing the current state of affairs in the LEO broadband satellite sector--which is interesting? The short review is not covering companies like SES/O3b MEO or the GEO operators...although they appear to be in a quandary of needing to deploy more capable satellites but acquire them the same way they’ve done in the past--slowly. At least one is facing satellite manufacturing delays due to COVID-19.

Of the LEO broadband companies, OneWeb is coming out of its bankruptcy. Its new owners/investors appear confident the company has raised enough money to get the satellites for its first phase deployed. OneWeb has deployed 104 operational satellites. The company is working with telecoms in various countries, but there are likely not enough satellites in orbit for courting subscribers yet.

SpaceX keeps manufacturing and deploying Starlink satellites--nearly 1,100 by Tuesday. Late last year, it started a beta-test program for users, who had to buy the terminal equipment for $500 and then pay a $100 monthly fee. SpaceX is subsidizing nearly $1,500 for each terminal. Musk noted this month that there are at least 10,000 of those subscribers. And the evening before Telesat’s announcement (which might have been deliberately timed), Starlink began accepting $99 pre-orders for its service. That amount of money will help the company determine who the serious customers are, perhaps establishing an initial and somewhat reliable indicator of subscriber takeup of the service.

Amazon keeps pushing seemingly promotional descriptions of what its Project Kuiper service will do. And that’s about it.

That’s two operators with actual satellites in orbit (progress, considering Teledesic and others lack thereof) and one well-financed 800-lb gorilla shadow. OneWeb and SpaceX are in the lead compared to Amazon and Telesat. Both can manufacture satellites at rates that make Thales Alenia look slow. While OneWeb’s initial phase of satellites is set in stone (and maybe too small to implement significant changes), SpaceX is aggressively adapting its satellites. The latest batch of 60 Starlinks (actually, ixnay on the 60 satellites—it was the 10 Starlinks on the Transporter-1 mission that had optical—sorry about that) has optical inter-satellite links (and Musk noted all Starlink satellites deployed from 2022 on will have OISLs).

While the two companies have made it significantly further than their predecessors, it’s still not clear they will make enough money to operate a sustainable business. Can SpaceX keep subsidizing sophisticated user terminals (more antenna analysis here) until the actual costs come down? Musk indicates at least a year of negative cash flow is in the cards for Starlink. Will OneWeb’s strategy of working with telecoms and its new investors’ low acquisition costs keep it from another bankruptcy?

And those are only a few of hundreds of questions surrounding the strongest players in the LEO broadband satellite space so far. So, what is it that makes Telesat believe it can achieve parity (at the least) without going bankrupt? What makes it think that using fewer, higher-costing satellites will still allow it to become successful? Is it a case of Blu-Ray versus HD-DVD (for older folks--VHS versus beta)? Are Telesat’s modems, antennas, and OISLs better than Starlink’s?

More to the point, will customers care?

Groundhog Day

Telesat believes the type of customers it’s courting will make Lightspeed profitable. At least, that’s what the company’s infographic informs us:

“Lightspeed delivers unsurpassed performance at transformative economics for Aeronautical, Maritime, Enterprise, Telecom and Government customers”

In plain-speak, Telesat intends to be a commercially-run network for businesses and government. However, that goal is not a change from what Telesat’s leadership messaged when it began toying with Telesat LEO in 2016. Back then, the company’s CEO and president, Dan Goldberg, gave his take about prospective markets for Telesat LEO during an interview:

“We think it will be extraordinarily well positioned for government users, for anybody with a mobility application, and for users in rural and remote areas.”

Telesat’s reference to mobility certainly encompasses aeronautical and maritime. Government users are still in the mix, too. But the poor folks in rural and remote areas are out of luck (they are, after all, potentially being catered to through OneWeb or SpaceX). Nothing changed in Telesat’s outlook of who its customers should be after six years of hemming and hawing.

Is adherence to that earlier vision justified?

Aside from Amazon, OneWeb, and SpaceX as competitors, the Europeans are studying the possibility of deploying a LEO communications constellation. The U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD) Space Development Agency (SDA) is already working on a LEO networked constellation as well, which it will begin deploying before Telesat does. The DoD already has its own expensive communications satellites and contracts for services with existing communications satellite operators. Would these groups be the customers Telesat is targeting for its Lightspeed satellites? Even with its fleet of satellites, the DoD would likely welcome lower latency communications and test Lightspeed. But would it rely on Lightspeed, which a company in another nation operates?

Telesat will be fighting the GEO/MEO satellite operators for the mobility business. Passenger service companies like American and Delta have already committed to equipment installations for one particular GEO operator. It’s also unclear whether data latency is the biggest concern for the aviation business or ships. If it isn’t, Telesat will need to be aggressive with its pricing and equipment installation services.

There are a few factors in Telesat’s favor: RF spectrum priority rights and explicit government backing. However, OneWeb also enjoys those benefits, the latter resulting from its bankruptcy filing. Neither one appears to give an edge to OneWeb so far. Still, I suspect the U.K. government would step in financially to keep OneWeb from failing again (a scenario that may not happen with Starlink).

None of the information above answers why Telesat is moving ahead with Lightspeed. If anything, the constellation’s technology, features, timing, and market plans raise more questions, as they don’t appear to give Telesat any significant edge. And, while the announcement is another step for Telesat, it’s far from actually fielding an operational constellation.

Comments ()