Containerization and Cargo Ships (or, why The Launch is Too Damn High)

New companies enter the space business with a “grand idea.” The grand idea describes what a startup believes will be the secret ingredient to its success. More importantly, the grand idea must excite investors, specifically those with enough knowledge to be dangerous and have an uncritical attitude towards anything space. Each new company has its own “not-so-secret sauce” it believes will help win the day. Focusing on launch companies, most of their ideas impact one facet of the business: launch vehicle construction costs.

Rocket Costs and Cargo Ships

Some companies paint their fast manufacturing as the grand idea of all ideas. Others think scaling up launch frequency (launching more often) will make rockets more affordable. A few rely on different technologies to build the rockets. Whatever their incentives and assumptions, ALL are attempting to decrease their rocket-building costs.

That focus on a single facet of the rocket launch business reminded me of a story, which may point to an incongruity or two between the launch companies’ focus and reality.

A few months ago, I had the opportunity to read Peter Drucker’s book, “Innovation and Entrepreneurship.” While reading it, I came upon Drucker’s concept of incongruities between reality and assumptions. The story Drucker used to illustrate his concept got my neurons firing, and you’ll probably see why after the following review.

For his concept, Drucker provided a cursory history about ocean-going cargo ships in the 1950s. Back then, freight costs using those ships were rising. For anyone shipping on cargo ships during that time, the shipping period between ports increased, primarily because ports became congested. Also, a lot of folks expected air freight to eat the shipping companies’ lunch.

During that time, much effort went into making cargo ships faster and fuel-efficient. In addition, the increased time between ports prompted some to use smaller crews. People made these improvements because of their perception of the shipping industry’s reality. However, Drucker identified their efforts as misdirected.

Why?

The industry had concentrated on improving one business aspect--the ship transporting cargo at sea--in which the costs were already quite low. And the improvements--faster, more fuel-efficient boats, for example--increased port congestion.

But the highest shipping cost was the capital invested into the ships. If the ports were congested, the waiting ships weren’t making money, and worse, the investment interest still had to be paid.

There are some obvious space launch industry parallels. Orbital rockets move cargo from one location to another (Earth to orbit instead of port to port). Building rockets requires high capital investment (larger, actually, than building cargo ships)--especially when legacy companies manufacture them. Startups are involved in disparate rocket-building efforts, with each attempting to gain efficiencies in a few examples listed below:

Rocket-building materials and processes:

3D printing

lean assembly lines

carbon fiber, stainless steel

Making rocket engines more:

Powerful

Efficient

Reliable

Reusability:

Parachute return

Propulsive return

While it may be evident to some, most of those efforts have everything to do with decreasing the capital costs of building rockets.

Following Footsteps Means Not Looking Around

These efforts aren’t misdirected in that reduced costs can ultimately help customers. But, unfortunately, many of their grand stories overhype their company’s potential. However, they aren’t offering customers new and cheaper capabilities. Is this because most startups and legacy companies make assumptions about the launch market instead of observing reality? What is the reality of the launch sector versus the assumptions we see? Are there assumptions?

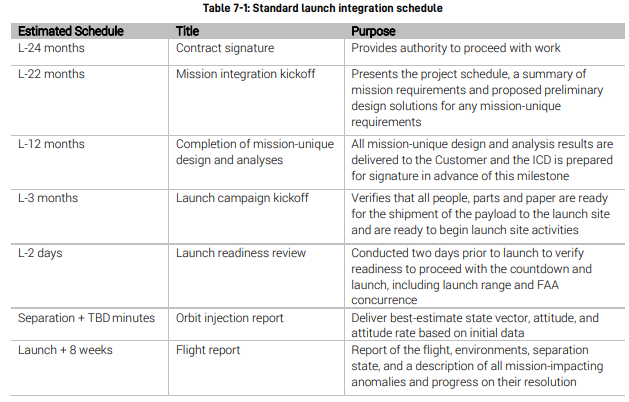

There are discrete segments in the parts leading up to a launch and within launch profiles. For example, referencing a few launch vehicle payload user guides help identify some of these segments. In SpaceX’s most recent Falcon 9 user guide, the company’s standard integration schedule requires customers to be patient. Over two years will have passed, from the customer’s contract signature to a few months after a launch. SpaceX identifies the schedule milestones like so:

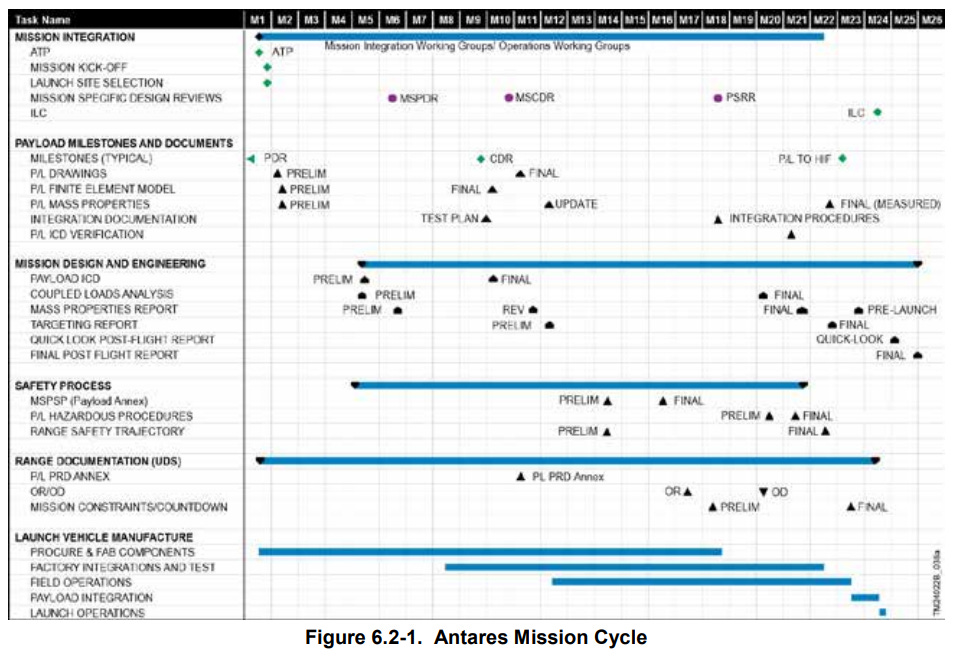

Northrop Grumman takes customers through a process nearly as long when it comes to Antares:

Of the two, I prefer SpaceX’s clarity. But then, I’ve always had a rational hatred of Gantt charts (it’s been over 100 years--surely, there’s a better way). In these schedules, we see several working assumptions. We see both companies accommodating their customers’ lengthy satellite manufacturing schedules. Both indicate that a few customers’ satellites may require some “rocket-tailoring.” We see two years’ worth of verification and reviews, primarily to give customers peace of mind.

If cargo ship companies scheduled customers this way (I don’t think they do--I am not a cargo ship expert), all shipping would slow to a trickle or stop.

At a guess, both schedules take inspiration from one source, the government. Traditionally, government customers didn’t (and still don’t) mind waiting for a launch. The lengthy process helped it with a few things--it provided the appearance of a deliberative risk-diminishing pace. More importantly, the government agency could spread the program budget out over the years. And as noted in other analyses, one of those government satellites costs at least as much as the average Lompoc, California ranch home (sometimes more than three ranch homes). That was the reality (and still is, based on NASA’s program and project life cycle guide).

As with every government-focused system, there are probably a few efficiencies to be gained by not using the system. And some customers would be OK with eliminating it. The whole point of a rocket is transportation. Any person can tell you that waiting for long periods, whether for a rocket launch, a cargo ship, or a subway train, is undesirable. At least the waiting subway passenger doesn’t have to deal with the endless reviews. By the way, based on Rocket Lab’s guide, the company seems to understand this opportunity as its whole schedule requires just one year--half that of SpaceX and Northrop.

This analysis isn’t about company integration schedules, although comparing them exposes opportunities for those willing to seize them. They do, however, demonstrate that perhaps the realities of commercial customers are different from when those kinds of schedules originated and the government customers that inspired them.

The other half of Drucker’s cargo ship story

Instead of tweaking the aspects of shipping cargo across oceans--which Drucker noted were already quite low--, it made sense to research, understand, and tweak the aspects that were cost-sinks--the ports. Finally, someone figured out the industry’s reality and implemented a simple concept: loading cargo on the land (in containers), then quickly stowing the containers on the ship. The pre-loading resulted in a quick ship turnaround in port.

Before that simple idea, the cargo was loaded a piece at a time. Grain, for example, was transported with no packaging, filling a ship’s hull. Likewise, manufactured goods were loaded one at a time, then lashed to the ship (to keep from shifting). The reverse happened when the ship arrived at the cargo’s destination port. The concept, containerization, streamlined that part of the shipping industry’s reality: slow loading and unloading in port.

Drucker noted this idea and another, roll-on/roll-off type cargo ships, changed the industry dramatically:

“Freighter traffic in the last thirty years has increased up to fivefold. Costs, overall, are down by 60 percent. Port time has been cut by three-quarters in many cases, and with it congestion and pilferage.” (page 91)

Imagine rocket traffic increasing fivefold in the next thirty years with corresponding falling costs. But the reality is that the space industry’s cargo ships, the rockets, spend most of their time not in port but a factory. That state of affairs indicates that the launch industry is far from mature. But, on the other hand, it also indicates the existence of plenty of opportunities.

One company is deviating from those traditional operations while launching rockets at a much lower cost than its competitors. That people question and dispute the company’s method of recovering capital investment costs is to be expected. One incongruity, however, is the broad (and perhaps mindless) acceptance of most launch service providers recovering capital costs by charging customers for the privilege of throwing away a rocket every launch.

Choose Your Own Reality?

Some may view launching rockets this way as better than having no access to space at all. Of course, all nations with launch capability gravitated towards launching rockets that way. But it also seems shortsighted and wasteful--the equivalent of sinking a cargo ship after every successful crossing. Moreover, if cargo shipping companies operated this way, the process would jack up shipping prices and wait times (imagine building a cargo ship for every crossing). However, on the bright side (because the process would be so ponderous), shipping ports would likely never be congested.

Of course, a person could argue that manufacturing cargo ships is the point, with transportation enabling that building. That kind of thinking believes that cargo shipping exists at the sufferance of the workforce. To make the ships more durable and maybe even use them more than once would result in fewer people building cargo ships. Therefore, it would be inconceivable for a company to build cargo ships that can cross the oceans more than once.

A few rocket launch service providers use this argument to justify rockets spending more time in factories than in operations. Thankfully, such arguments failed the common-sense test in the shipping industry. But it’s enlightening to note that the older launch companies arguing for building rockets instead of running a transportation business don’t appear concerned about making launch less expensive.

Rounding back to the new orbital space launch service companies’ focus.

As noted earlier, most are attempting to cut rocket manufacturing costs, which is commendable but not revolutionary. The focus on that launch service facet must change because commercial customers don’t care about anything but the service--transportation. However, this industry may still be too immature to address other facets, an incongruity with today’s “growing commercial space” narrative.

The reality is that launch still costs too much for most satellite operators because the launch operator must recover the costs of a rocket used only once. Since many newly proposed companies appear to eschew reusability, it solidifies the path they must use, including tweaking launch construction costs for not much return. Still, for them (and for those exploring reusability), there may be other aspects of the business worth looking at to help gain a return on their investments.

Comments ()