China’s Launch Trends and Spacecraft Deployments

When it comes to China and its space activities, things get complicated. First, the U.S. national security worries about China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) launching more often and deploying more satellites. Then there are commercial worries about China’s space companies offering more for less, even as they deploy more spacecraft. Even NASA hops on the “worry tram” circuit around China every now and then.

China is a convenient punching bag, especially since the nation dares to have space ambitions. First, the nation’s industry is aggressive and notorious for flagrant copying of everything. Eventually, copying slows down, and companies begin producing products with their own merits (see 3-D printers and phones), but there’s a sense (justified) that China’s government encourages those practices. There’s also the language barrier, which fosters suspicion and spurs fears of “the other.” This happens on all sides.

Worse, China dares to stand up for itself, which offends the sensibilities of those who believe in alternative jingoistic narratives. The fact that it has the means not only to defend itself but also to project its power intensifies the offense in the eyes of some citizens not from China. That its space industry is separate from the rest of the world’s space efforts would not just be a weird artifact in their eyes but ominous, too.

To be clear, there are all sorts of things about China to worry about, and its government is not an innocent with no stakes in the international poker game. Taiwan, for example, should be concerned, especially after seeing how China is handling Hong Kong. Its military’s plans for space are also worrisome…but then, U.S. military space plans would also disturb anyone not a U.S. citizen or ally. And there is still reporting demonstrating that its government considers human rights as important as a consumer finds an EULA–which is not at all.

However, the same self-interested parties have repeated many of their worries about China before (in some cases over decades), making the fable of “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” seem less like a twisted morality tale and more like an instruction manual.

So, is there a space wolf to worry about? Let’s review some numbers, most of which will be current up to and including December 9, 2024.

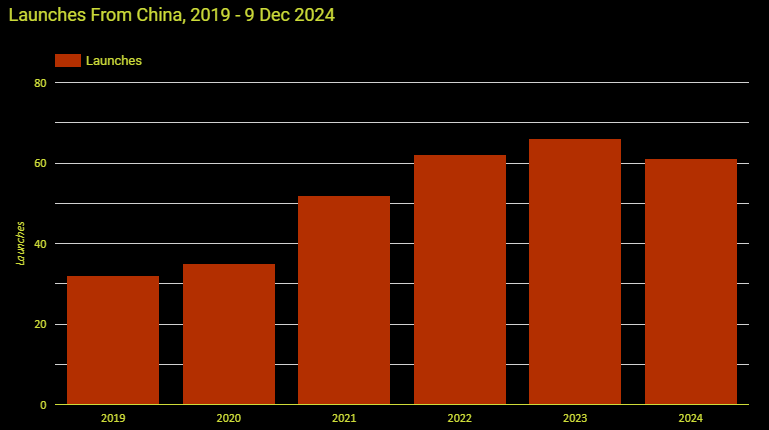

Launches: Increasing

As far as launches from China are concerned, they have been growing. Since at least January 1, 2019, successful orbital launches from China have increased nearly every year, about 17% on average, except for 2024. The year isn’t quite finished, so China’s launch providers could launch six more rockets to orbit in the next 2-3 weeks. They’ve launched substantially more rockets in December during each of the two years prior than in December 2024, so the probability of doing so is much higher than zero.

The most significant jump is from 2020 to 2021, from 35 to 52 orbital launches, a nearly 49% increase. It could be that the pandemic suppressed launches from China in 2020, and the growth slope would have been smoother between 2020 and 2021.

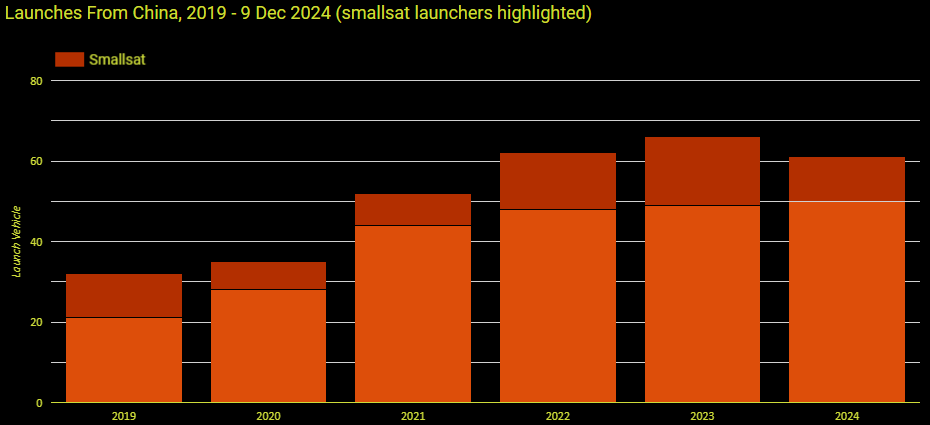

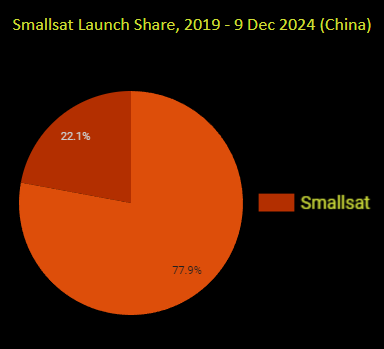

For those wondering whether China’s smallsat launch providers conducted most launches each year, the data below shows the answer to be “no.” While they took significant shares of launches each year, the highest share of smallsat launches (1,500 kg or less) for the period covered was in 2019, taking ~34%. Most orbital rockets launched from China during that time could lift more than 1,500 kilograms.

The overall share of smallsat launches during that period was 22%.

So, yes, China’s launch providers are not just launching more; since at least 2019, they have launched more than the prior year. We’ll see for 2024.

Spacecraft Deployments: Increasing…but…

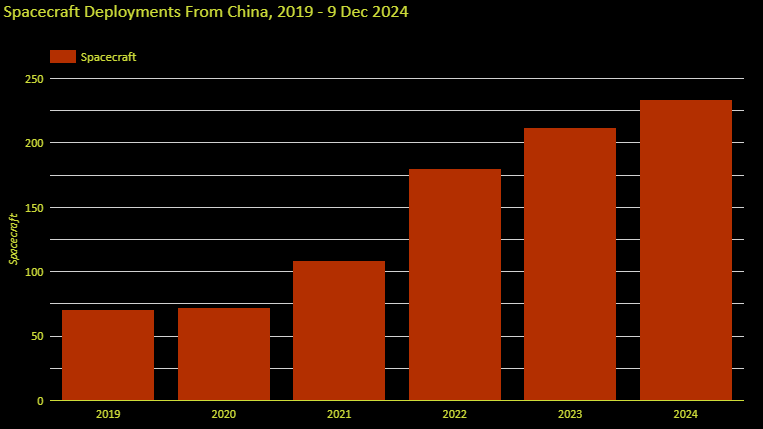

Increased launches indicate increased spacecraft deployments. That’s also what the data exposes (below), averaging about 36% annually.

The chart is strange, however. Compared with the launch chart, there is a small corresponding spacecraft deployment jump from 2020 to 2021. However, a more significant jump follows. Between 2021 and 2022, spacecraft deployments grew 65%. At a guess, there may have been a pandemic-induced delay in smallsat manufacturing in China, perhaps because of supply-chain challenges exacerbated by smallsat market growth. That growth continued, as China’s space operators have already deployed more spacecraft than ever in 2024.

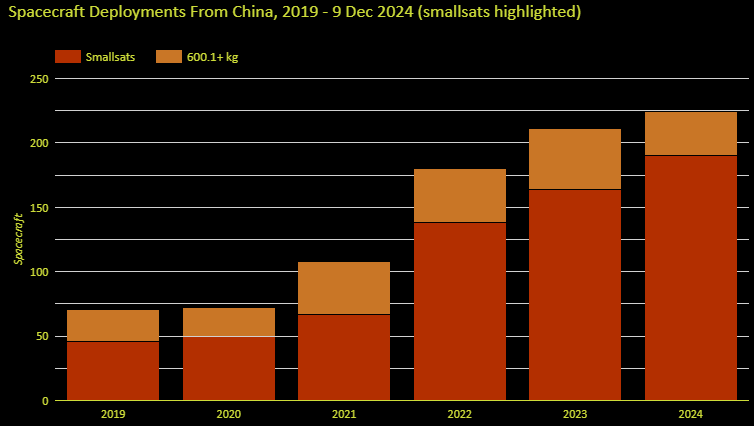

However, some more strangeness follows. First, while China’s smallsat launch providers launched a small share of launches, smallsats themselves (600 kg or less) were most of China’s spacecraft deployments.

The switch makes sense to those familiar with smallsat launch economics, China’s launch services, and rocket inventories. Smallsat launchers always have a higher cost-to-mass ratio (at least in the rest of the world). There’s no reason to believe those economics differ for China’s smallsat launch services. There’s also no reason to think China’s smallsat operators would choose more expensive smallsat launchers when so many alternatives are available (below).

Only in China: Launch Competition and Variety

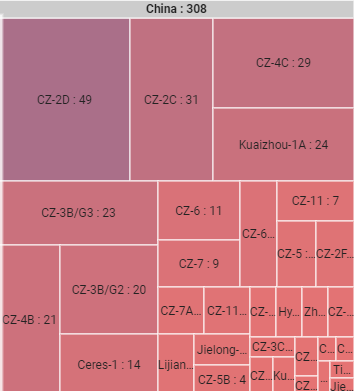

The above treemap includes all successful launches from China from 2019 through December 9, 2024. Spacecraft operators theoretically could choose from over 30 launch vehicles during that time. Most have decent reliability, as well, so why wouldn’t a space operator choose the less costly and more reliable rocket?

While the breadth of rockets available in China during that time was impressive, the types of rockets available also guided selection. It’s another aspect of the smallsat launch discrepancy: nearly 60% of the rockets have a maximum upmass below 5,000 kg (almost half of those can lift only 1,500 kg or less). Seventeen percent have a maximum upmass below 10,000 kg (lifting at least 5,000 kg). The remaining 23% can lift 10,000 kg or more.

From 2019 through 9 Dec 2024, 22% of China’s rocket inventory were dedicated smallsat launchers, but nearly 75% of spacecraft deployed from China were smallsats. That ratio indicates that smallsat launchers were not the primary means for deploying most of China’s smallsats.

All of the data above is to say that China’s space operators are doing precisely what the rest of the world’s space operators seem to do when the service is available to them–they are ridesharing rockets. Smallsat launchers have been used for rideshare; however, larger rockets are a more effective and less expensive option. India’s PSLV-XL, Russia’s Soyuz, and the U.S.’s Falcon 9 have demonstrated this.

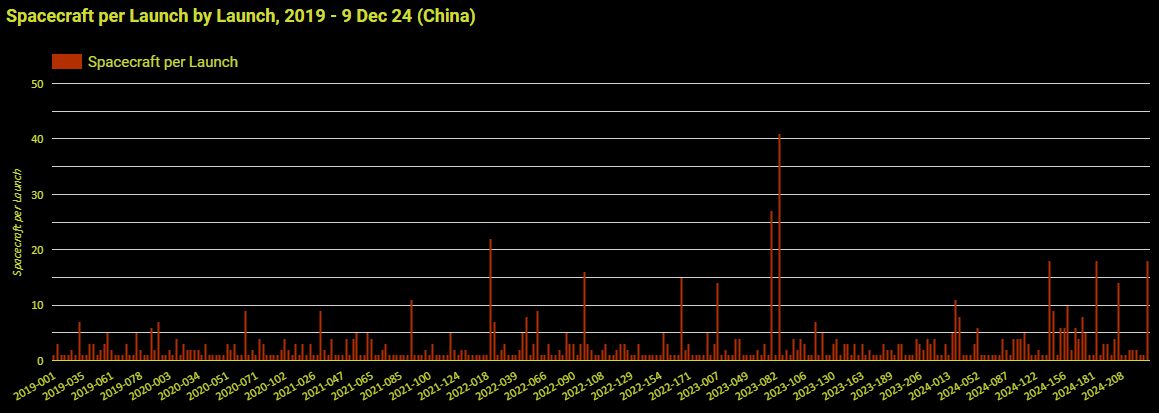

And ridesharing is seen in the data for China, which is admittedly nearly illegible in the chart below. Every launch above the bar for a single spacecraft was a rideshare, and China’s spacecraft operators used a lot of rideshares. You can even distinguish the three Qianfan deployments on the chart’s right.

Ultimately, people are correct that China is launching more often and deploying more spacecraft. The data shows this, and based on the news, no reader is probably surprised at how active China’s companies and space organizations are. The data also indicates that reusable rockets are not required for a rideshare launch to be profitable; otherwise, the rideshare launches would have decreased over time instead of increasing. Reusability, however, could make rideshare more affordable and yield more profit.

While China’s launches are increasing, they aren’t coming close to growing at Falcon 9 rates. Falcon 9 launches for 2024 are currently over double all of China’s launches for the same period. Hilariously, China’s space operators are doing exactly what the rest of the world’s space operators seem to be doing: generally forgoing smallsat launcher options. They aren’t buying the smallsat launch narrative any more than anyone else (aside from venture capitalists).

It’s somewhat comforting to see trends similar to those of the rest of the world, likely because of similar economics, displayed in China’s space industry. Even though its industry stands apart from the rest of the world, it is still subject to the same market forces—that’s my superficial read of the trends in China from the past few years.

Of course, there is that warning to be vigilant of those in sheep’s clothing. However, the data indicates that the wolf beneath might still be more kin than a monster for some of China's space activities.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), please share it. I also appreciate any donations (I like taking my family out every now and then). For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU from me and my family!!

Either or neither, please feel free to share this post!

Comments ()