A Future Without ULA?

This article continues my section from 2023: Pointing to 2024’s Space Activities. The section, subtitled “Downsizing From Two U.S. “Big Launch” Companies to One,” suggests that there will ultimately be one major launch company: SpaceX. Because ULA is for sale, its survival is unclear, even (perhaps “especially”) if Blue Origin buys it. As Blue Origin hasn’t begun launching orbital-capable rockets yet, all companies with large spacecraft to launch will go to SpaceX. The small ones have already stampeded in that company’s direction.

I have a few more observations to make, ones I left out of the “Space Activities” piece because putting them in would have made the summary far too long.

Vulcan Launched!

To be clear, the United Launch Alliance’s first successful Vulcan launch on January 8, 2024, is an accomplishment the company and its people should be proud of for several reasons. Foremost–it worked despite using new rocket engines and a new rocket design. It also now has a rocket that doesn’t rely on Russian-made RD-180 rocket engines, which is extremely important today, considering the Russian government’s war with Ukraine. Vulcan also provides a milestone pointing toward the possibility of becoming a part of the global launch community.

That first fact–Vulcan worked–can’t be removed from ULA’s accomplishments. Most of us (maybe) would like to believe the new rocket launched successfully because of hard work, ingenuity, and know-how. But other companies have all those characteristics and didn’t manage to conduct a successful orbital launch the first time out. So maybe a little luck was involved, too.

The second aspiration of having a rocket that doesn’t rely on Russian-made engines is a bit more…complex. And part of that complexity has everything to do with its new engine-supplying partner, Blue Origin. ULA’s choice to use Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine for Vulcan seems wise, especially when it moves ULA further away from using Russian engines. However, the company made trade-offs in deciding on the BE-4 for Vulcan. First, ULA bought into an engine that hadn’t been demonstrated as fully operational. And second, it bought into an engine from a potential competitor.

Wherefore Art Thou, BE-4?

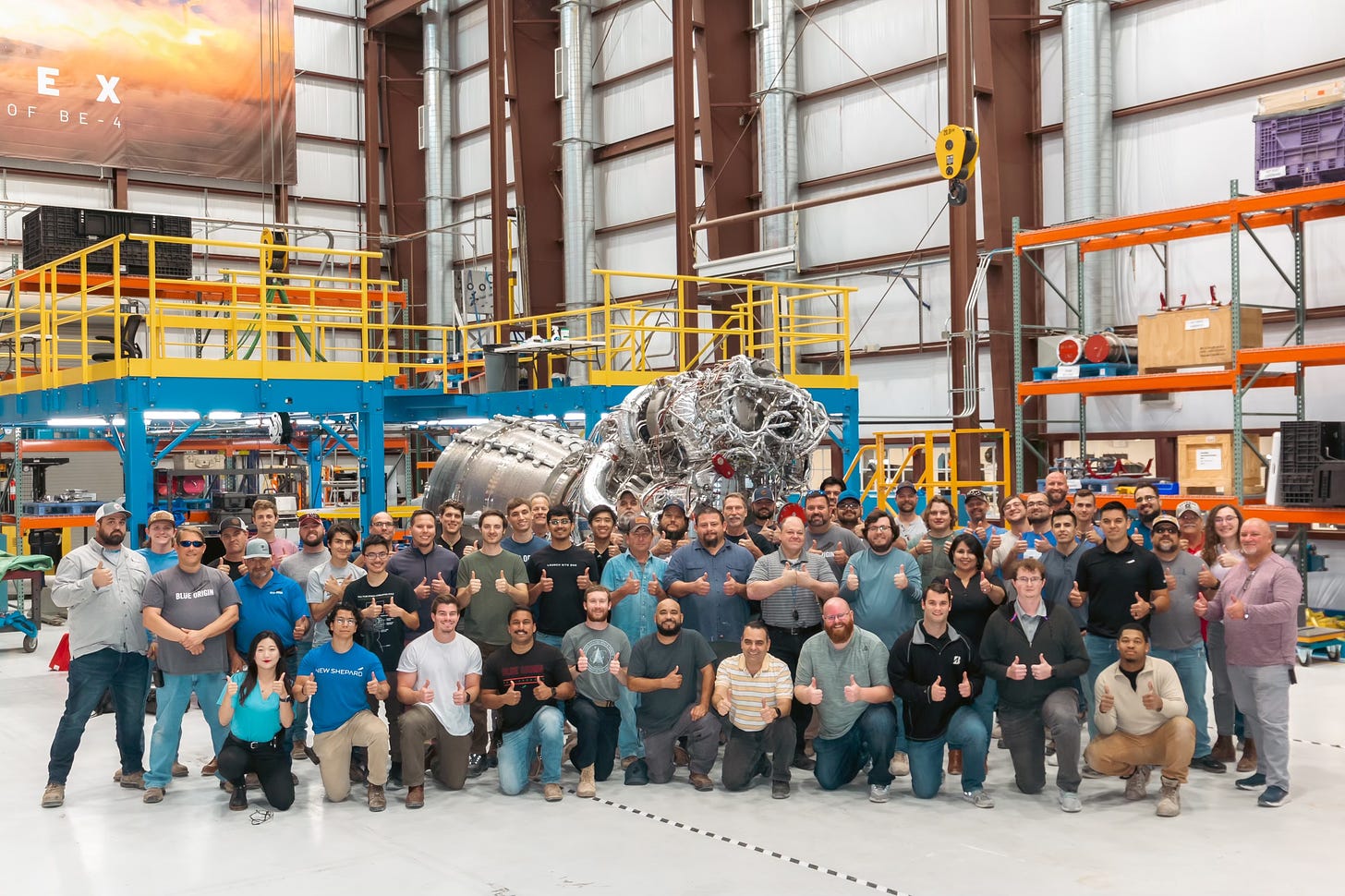

For the first trade-off, the following pictures from Blue Origin’s Twitter/X feed might inadvertently highlight the problem. Do you see it?

Maybe it’s more evident if I compare them to a SpaceX picture (below), including its Raptor engines. I promise, there’s a difference and a point.

The Blue Origin pictures show more people than engines in what is supposed to be a rocket engine factory (whereas SpaceX’s picture shows the opposite—there are two people in there, but the engines obscure them). Perhaps Blue Origin’s pictures are merely anecdotal, but based on how long ULA waited for its first pair of Vulcan engines, maybe they aren’t. And that’s my primary reason for worrying about ULA.

The Vulcan’s engine and Blue Origin itself primarily drive uncertainty surrounding ULA’s Vulcan. That uncertainty is one of the challenges with that sale. Buying a rocket company with a small supply of legacy Atlas V rockets might not appeal to buyers. And a single successful Vulcan launch does not mean ULA has the engines to manufacture more. Even as ULA’s Tory Bruno mentions plans to build 25 Vulcans a year, he’s not being dishonest (probably), but he’s also not telling us whether those rockets will still be waiting for Blue Origin’s engines.

Blue Origin still needs to provide firm numbers on how many BE-4 engines are ready to go and how many it aims to manufacture daily. If either number were more than two, the company would have advertised the fact, just like SpaceX. The engines Blue Origin is supposed to be manufacturing don’t appear to exist in any meaningful number, and with ULA hedging the date of the next Vulcan launch, well, there’s reason for doubt for ULA’s and Blue Origin’s survival.

Conflicted Concerns of the Competition

ULA relies not just on an external engine supplier (Blue Origin) for Vulcan, but that supplier is also a potential competitor to its business. It may have decided to do so because it didn’t perceive Blue Origin as a threat. Maybe it was desperate to get some kind of “new space” veneer on Vulcan by using an engine from a new space company. It helped that it cost less. While both of those latter guesses seem ludicrous, ULA’s head engineer resigned for bluntly saying just that. The truth hurts (business).

Potential ULA buyers should have genuine concerns about relying on the BE-4–especially if they continue to be a sticking point in Vulcan’s launch campaign. The BE-4 is still a weakness that could sink ULA’s plans, even though the engines performed nominally during launch.

What should also concern buyers is the possible conflict of interest and actions stemming from the Blue Origin/ULA agreement. What happens when Blue Origin decides that Vulcan is too competitive or successful against the company’s ghost rocket? Would increasing the price of the engine to ULA make New Glenn more attractive?

Those potential buyers may then have to consider the possibility of getting out of that deal. Otherwise, they will have a rocket company full of rockets with no engines. Or maybe they get an ironclad guarantee from Blue Origin that it supplies its BE-4 engines for $XXX million for the next decade. That would allow the new buyer time to design and maybe develop a competitive launch system that is not reliant on Blue Origin for its engines.

And if Blue Origin Bought ULA?

Blue Origin is among the potential buyers. There is the fundamental question: WHY is Blue Origin contemplating buying ULA? Is it to take out the competition? Is it a talent acquisition? Blue Origin already has thousands of people working for it and could buy away ULA’s talent. Is it the Vulcan rocket? Blue Origin is working on its own rocket. To fall back on Vulcan would be admitting New Glenn is fiction. Maybe it’s for ULA’s rocket factory in Alabama? It’s supposed to have a modern factory in Florida. The more likely possibility is that it gives Blue Origin access to military launch contracts.

However, if Blue Origin became ULA’s new custodian, whether either company would survive the acquisition is unclear. None of the above guesses are predicated on ULA coming out of the acquisition unscathed because Blue Origin doesn’t need Vulcan.

Of course, there’s also the fact that the company has never conducted orbital launches (but neither have the other buyers). Also concerning: based on Blue Origin’s management history, it’s unclear if the company would even know what to do with sudden launch capability (if the engines are available). Maybe they allow ULA to fulfill its NSSL contracts using Atlas V without interference, but once they’re gone, that would be the end of ULA.

The worst case, though, is the potential elimination of both companies if Blue Origin bought ULA. Blue Origin would be increasing its workload through that acquisition but still hasn’t established New Glenn as a working rocket. Nor has it demonstrated that the company can mass-produce reliable BE-4 engines. The latter would be helpful if Blue Origin decided to keep Vulcan running for some reason.

Conducting ULA’s launch operations and developing a reusable rocket (Blue Origin’s perpetual hell) also creates a split focus for the company and its managers (not great for a newish company). The acquisition would be a distraction for Blue Origin, which could kill its rocket development efforts and acquisition (because it relies on the quirky engine). It will gain not just ULA’s assets but the company’s overhead, too, which means spending time and money from Blue Origin’s coffers.

Since the company has displayed a remarkable inability to walk and chew bubblegum at the same time, it’s difficult to believe it will also come out of the acquisition unscathed. Maybe the company’s new CEO changes that, but cultural shifts are hard, especially if Blue Origin believes it doesn’t require them.

Ultimately, ULA’s future is not clear. Muddying its future is the fact it’s for sale now. While potential buyers already understand they would be fighting against SpaceX’s dominance and what it brings to launch services (low prices, launch reliability, launch accessibility), they should also be aware that the challenges to ULA are already occurring.

Those challenges are posed by a potential competitor, Blue Origin, which has been slow in developing an engine critical to ULA’s business. The fact that this competitor is hobbling its launch competition should be questioned. Whether intentional or not, that slow development could impact ULA’s sale price because again, it may not have engines for its rockets. That sale price might land ULA in Blue Origin’s lap, which wouldn't be healthy for ULA, either.

Based on those challenges, ULA’s future is far from assured.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), any donations are appreciated. For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU!!

Comments ()